12 May 2021

$1.3 billion digital health budget commitment, but to what?

In a big-spending budget, digital health got a lot of money, but without establishing a common strategic framework for such a spend, and a framework that aligns all system stakeholders with how web sharing and open systems technology is rapidly evolving, we risk wasting this important opportunity.

On first inspection, the commitment by the federal government to digital health in this budget is the biggest by a historically long margin and should augur well for the sector, over the forward estimates at least.

Depending on how you read the commitments, the spend might actually be well over $2 billion. Some spends are likely to be bigger than even the budget is revealing. For example, surely they will extend telehealth past December this year and this would add a huge amount to forward estimates, and surely a good chunk of the $365.7 million being promised to improve access between aged and primary care is going to be spent on digital systems.

So what could be wrong with this?

You don’t have to dive too deeply, even into the major commitments, to see that the spending is disorganised. It is perhaps a sign that the government didn’t really have the time to think about how they were spending the money before they committed it because of the nature of the budget, which is one designed to pour money rapidly back into the economy, create lots of jobs and win the next election.

Most of the component parts of the spend, even the big chunks, have no underlying framework that would help align each of them in some way so that there was sensible co-ordination across sectors such as aged care, mental health care and primary care.

There is no attempt to align what is being spent in one area with another in terms of a common technology framework or standard, and so none of the spends are committed in any way to talking to one another efficiently, or even using technology that is likely to future proof the spends in terms of changing technology in the sector.

What would it look like if we spend up to $200 million on digital health platforms in mental health that didn’t talk to our core digital health systems – to GPs, or hospitals, or even the My Health Record?

It is not too late to address the issue, but if it isn’t addressed, we are going to end up with a lot of component builds in systems that simply don’t align and end up causing more complexity in an already overly complex system. This isn’t what digital technology is designed to do these days.

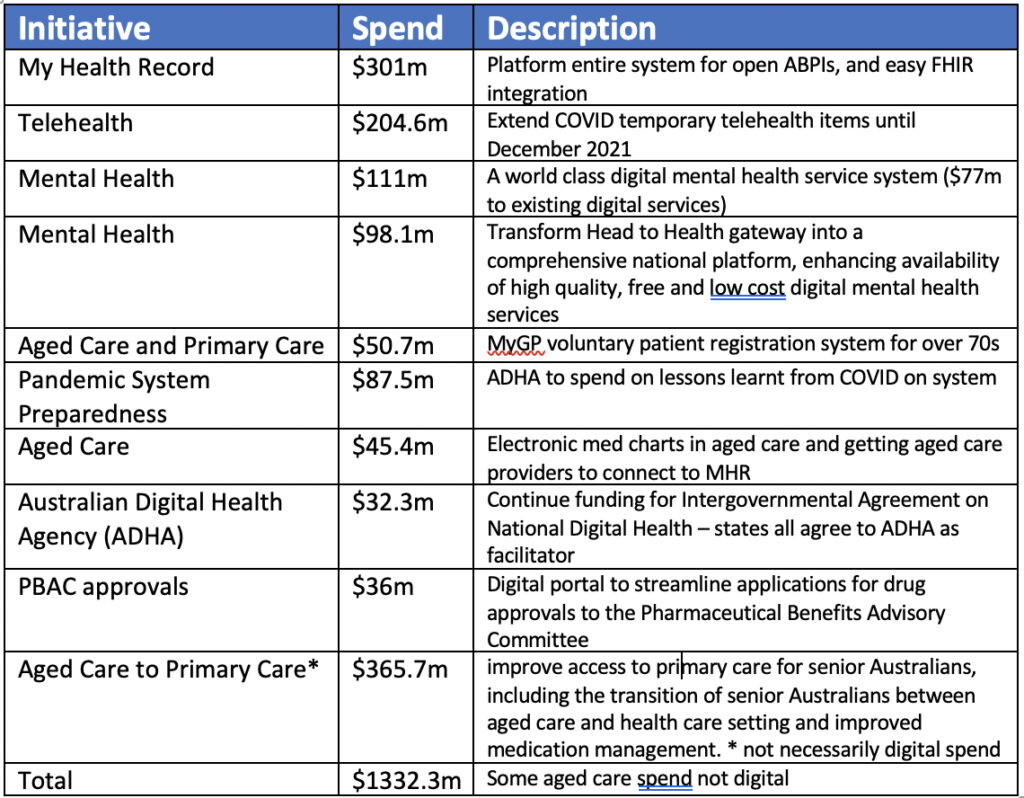

Let’s look at just a few of the bigger spending commitments and how they might align or synchronise and be used. (A chart of all the major spend announcements is produced further below):

- $301.8 million for the next wave of the My Health Record (MHR)

- $87.5 million for the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) to spend on lessons learnt from the COVID-19 pandemic to help improve system preparedness and responsiveness

- $46.4 million to roll out electronic medication charts in residential aged care facilities, and drive use and integration of the MHR

- $111.2 million to create what the budget claims will be a “world-class digital mental health service system”, including $77.3 million “to provide support to existing mental health services”

- $365.7 million to improve access to primary care for senior Australians, including the transition of senior Australians between aged care and a health care setting, and improved medication management

At least four of these five items and over half-a-billion of the spend is focusing each spend back to the MHR in some way.

At this point, and without a more considered and proper strategic framework for developing all these disparate but vital digital services, are we really still going to try to make everything talk to the MHR as first base?

In this respect, the MHR has become our default digital framework or standard for the system – at least as far as government spend is concerned.

But the MHR is not a strategic framework or standard that addresses how all our digital health systems move in a line towards the fast-evolving web-sharing digital ecosystem.

It is a solution – not a standard.

Whether or not you back the potential of MHR to do what the government says it’s going to do, it is not a framework that would guide all future development of digital solutions in health towards being far more interoperable, no matter what solution they were.

It is simply the government’s idea of a solution to the problem of data sharing, which the government often has to incentivise people artificially (with money) to talk to. It doesn’t guide any other solutions, and when the government insists other solutions talks to it, it can actually inhibit those solutions because the logic, architecture and sharing protocols of the MHR are mostly out of date now.

At present, any component of money committed in this budget can be spent on a technology solution that ultimately won’t communicate easily with other solutions, and may or may not be future proofed in terms of web-sharing architecture and protocols.

In such a strategic framework vacuum, any of the money from this $1.3 billion and more can be spent on solving digital health issues, even by applying very old technology to a problem. Such technology will leave some systems, potentially highly important ones, such as a national mental health platform, isolated from talking to other key health data systems, the data of which is starting to be sharable within the health system.

You could argue that $301 million for re-platforming the MHR by making it accessible easily via cloud-based APIs, and Fast Healthcare Interoperable Resources (FHIR) interfaces, is modernising the MHR so it can talk better to modern and evolving web-sharing technology.

And it might.

But if the government is going to spend so much money getting alignment to evolving technology on its one grand solution to our digital health problem, why won’t it mandate in some way that all other systems have to do the same thing?

At the moment all they seem to mandate is that systems somehow send their data to their centralised solution.

It might be useful making the centralised data in the MHR far more accessible via a modern set of web-sharing interfaces.

But $301 million is a lot of money to spend on top of the $2 billion already spent to keep an old technology solution concept in play.

Even if the government succeeds in polishing the largely landlocked and disorganised data sets that sit in the MHR far more accessible the “MHR solution” will still have a whole lot of problems associated with it, issues we probably wouldn’t need to worry about in other solutions:

- All points of the healthcare system currently have to write systems and produce data and feed that data to a central data centre that is the MHR. Then, when they want data back, they need their system to decode the MHR in some manner to get data back in a useful format. The logic and structure of MHR doesn’t make much sense anymore as a result. Now mobile phones can capture and manage all the data a patient needs, as and when they actually need it, as they wander around the system, so long as the component-distributed databases are building to modern web-sharing standards.

- After a $2 billion spend and nearly 18 years of effort, no one uses the MHR still. Not patients and not healthcare providers. The major reason is it isn’t built to be useful in their healthcare journeys. It will be very telling over the coming year to see how many patients and healthcare providers take up electronic prescribing, and products such as FRED IT’s My Script List (MySL), which is a more modern distributed cloud solution to medication management that shares data between a GP, a patient and a pharmacist via a national Rx echange, to ensure medication management is efficient and accurate. This system doesn’t require the pharmacist, patient and doctor to do anything other than switch it on in their patient management system, dispensary system, or consumer app. It’s easy, accurate and live.

- The MHR is a honey pot data set that will eventually be hacked in a major way, as all the experts acknowledge.

But let’s not harp on the MHR too much here. In a manner, it’s not the problem anymore.

It’s just another solution, and at least the government is committing itself to updating its old technology so it can talk to a cloud-based web-sharing ecosystem into the future.

The worst you might say to this is that it’s a lot of money that might be better spent on developing a framework and guidelines for providers and vendors in the entire system, so everyone understands the rules of the future, the terms of transition, and perhaps, deadlines to extinguish old technology that is hampering proper sharing of data in our healthcare system.

Maybe the MHR will eventually start helping a lot of healthcare providers and patients in the future if it re-platforms itself. Maybe, if it is re-platformed in time, it will serve some sort of transitional role in supporting a patient data set while all the component parts of the system align to web-sharing technology.

But the stark truth for the ADHA and the government is that most of what is in the MHR today, and in the near future, will eventually be made directly accessible to a patient’s mobile phone and private health management system from distributed data sets in the healthcare system that a patient accesses. Such data sources include pathology results, GP patient management systems, immunisation records, hospital discharge summaries and so on. That this will almost certainly occur has been demonstrated in the technology rolled out on a patient’s active medication list through tokens and the Rx Exchange.

Interestingly, the ADHA had an important role to play in the development of this system. The system does not talk in any way to the MHR. So the ADHA must know what is going on here.

If we don’t come up with a well-defined framework upon which everyone participating in the digital development and maintenance of our healthcare system could understand and work , it would be easy to believe that in the not too distant future the MHR will naturally become redundant as a central database anyway.

You can see the start of that process in the Active Script List (ASL) program. In essence, a solution such as Fred IT’s My Script List has entirely bypassed the need for the MHR, and come up with something that GPs don’t have to spend any time administering, which assists pharmacists and aligns to their commercial objectives, and which patients or their carers will find easy to use on their phones.

But there is a massive problem in the country sitting back and waiting for this technology to eventually flow down hill, which in the end it always does, and get us to the right set-up.

We have, as a country, enormous imbedded legacy in our healthcare technology. And with this follows legacy in our policy and funding. All of this legacy will naturally do all it can to resist change.

If someone in Australia doesn’t stand up soon, as the governments of many Scandanavian countries, the US, UK, Israel and even some Eastern European countries have, and say, “we know this is really hard for everyone, but we must dictate in some way now a framework for developing all technology solutions in health in order to get to the future quicker because there is so much at stake”, then we are doomed to waste most of this spectacular spend on digital health in this budget, and doomed to waste a lot more after that.

To put it much more bluntly to government, we are doomed to kill a lot of people and cause a lot of suffering, which we could avoid through getting to the future of digital health much faster in this country.

If the government does get to this inflection point in thinking then it will need to give every stakeholder in the system – vendors and providers – a reasonable timetable to change their ways – a sort of “we leave no soldier behind” set of protocols.

Of course, such a promise would necessarily be a hollow one in some respects because this new technology is so efficient, and disruptive to systems and people, that there will always be some casualties, no matter how careful you are.

But that’s a risk equation that is easy to assess now. We are already too far behind because of the time we are going to need to take nurse providers and vendors to the modern world of health data sharing. The longer we leave this decision, the less time we will eventually be able to give to vendors and providers, and the more carnage there will be when the change does come.

It’s almost certain that, in the near future, solutions that are built to share data far more smoothly across the web, and to patients themselves, will save lives: systems such as My Script List, and apps like MedAdvisor, which are likely to be carrying such systems.

We’ve just committed a fortune to the future of digital health in this country.

But we haven’t provided anyone with a sensible framework or set of standards by which they should be spending the money.

Certainly, part of that problem is the MHR.

But even the MHR can exist if it falls into the right framework for a solution for the future.

But we don’t have that framework.

The UK has a version of it. They mandated almost three years ago that all digital health infrastructure had to be built around cloud functionality. The UK government has been a bit loose in how it specified this but it has at least specified it, and they are supporting big programs to help both providers and vendors move to an aligned and modern web-sharing ecosystem. They have a framework and some goals.

The US, which must be the most messed up and eclectic First World country in terms of efficient healthcare delivery and funding in the world, started the journey in a far more didactic manner five years ago with its “anti-data-blocking in healthcare” legislation regime.

As a result of this legislation and the changes that have to accompany it, the US the US is now moving rapidly too address interoperability across its whole system because all the stakeholders are very clear on what they need to do. If they don’t change in the required time frames, they will be breaking the law and someone might be going to jail – that’s how seriously it is being taken in that country.

The Australian digital health sector and the government aren’t necessarily backward or stupid here.

Both the UK and especially the US had significantly more distressed healthcare systems to address. Australia has always had a pretty good healthcare system. Politically and organisationally, it is extraordinarily difficult to get moving early on decisions such as these when there is nothing driving you or the system immediately to it.

But it’s a slow-boiling-frog scenario, and the way digital disruption goes, we are going to go from tepid water to burning platform before we know it. We almost certainly are going to get into trouble already, given our timing.

As things stand in Australia today, we are blowing in the wind in digital health.

If we don’t have a serious discussion around a better national framework for digital health technology development and its use, probably some form of standards, and maybe even some legislation to give the whole sector some impetus, nearly all of this new digital health money will be wasted.

One thing that is likely to happen if the various digital systems we are now all gearing up to develop aren’t aligned in some way, and don’t talk properly to one another and to the key databases in health, is that all the money being spent on aged care and mental health will be spent in a massively inefficient manner.

And in that, almost certainly, future lives will be lost.