9 August 2021

Chronic Insomnia – will digital health succeed when everything else fails?

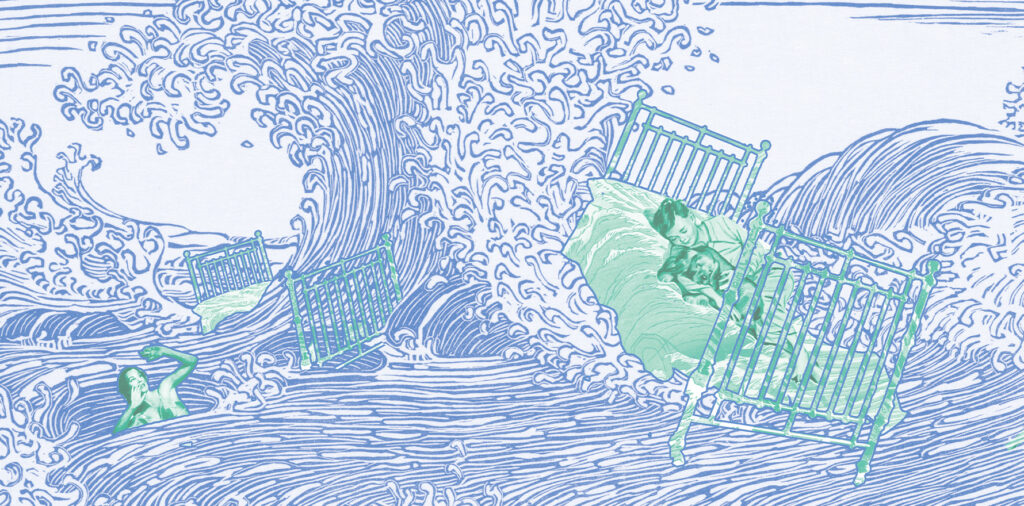

Marie* was not sleeping properly.

Which is normal sometimes, but not over a period of 12 months. Falling asleep was not the issue, it was the waking in the middle of the night, her mind racing with thoughts and not letting her fall back asleep.

Headaches and teeth clenching were regular visitors in her working day as a nurse and at night, and constant fatigue ebbed away at her concentration and memory, two vital skills to perform her job and role as mother to three school children.

She could vaguely trace the cause. Covid lockdowns had meant she had added the unwanted job of online classroom teacher for her children’s schooling. The grandparents would usually be on hand to lighten the load, but they had been immobilised by isolation orders. Tension accumulated in her body, and her mind felt more wired than tired. She really needed sleep – a full night’s sleep. But she kept waking in the night in a hyperaroused state, desperately attempting to fall back asleep and desperately failing.

‘Coronasomnia’

While some studies suggest we are sleeping more on average during the pandemic, there is strong evidence that for a proportion of the population, including Marie from NSW, the opposite is true. This pandemic is a tale of the sleepers and the sleep nots.

In 2019, the Sleep Health Foundation published a chronic insomnia report that indicated around 7 to 15% of the population had sleeping symptoms that could be classified as chronic or a disorder. That rate appears to have risen since covid began, according to research undertaken by psychologist Dr Melinda Jackson of the Turner Institute for Brain and Health at Monash University.

Dr Jackson has co-authored two papers that surveyed people in more than 60 countries on their sleep quality and the prevalence of anxiety and depression. The evidence for the sleep nots is clear.

“Our meta-analysis of studies conducted in 2020 estimates that insomnia prevalence has increased to 38% of the population, from pre-pandemic levels of 10%,” Dr Jackson told Wild Health. “There has also been a 58% increase in internet search queries for ‘insomnia’ since the pandemic began.”

Is it just a 2020 problem? In July this year, TV’s Channel 9 rehashed a story from 2019 on a sleep device designed by Flinders University researchers. The next day the lab behind the device received more than 8,000 calls and emails. It’s register of contacts prior to the story was less than 500.

A NSW Central Coast-based sleep clinic told Wild Health its daily patient list was full of covid-driven sleeping problems.

“We are seeing difficulty in separating work from home, as people are working from home more and it blurs into one,” Dr Dev Banerjee, a sleep physician at Lullaby Sleep, said.

“Over 80% of my workload is mental health and insomnia. Mental health does not disappear when the sun goes down, it morphs into insomnia.”

Anxiety and depression cloaks

Since the pandemic began, mental health cases and demands have risen sharply. But there is concern the role poor sleep plays in mood disorders is not being adequately addressed by GPs or the patients themselves.

“We have a problem in the sense we don’t recognise the impact insomnia has on mental health,” Robert Adams, co-author of the Sleep Health Foundation report and a professor in respiratory and sleep medicine at Flinders University, said.

“The idea that if you fix the mood disorder the sleep will get better, is probably shortchanging people, and really missing an opportunity to help with people where increasing evidence suggests a specific focus on insomnia might help,” Professor Adams told Wild Health.

Dr Giselle Withers, a clinical psychologist, said in the case of a patient presenting with both depression and insomnia, it was best to treat both conditions.

“There is research that shows that people who have residual insomnia, even after an effective depression treatment, are more likely to relapse. So, it’s important that sleep is treated as part of a general psychology intervention,” the Gold Coast-based clinical psychologist said.

The GP conundrum

In the past when a patient raised a persistent sleep issue with a GP, the GP would enquire to rule out rarer sleep disorders, like sleep apnoea and restless legs, and then diagnose insomnia and hand the patient a prescription for melatonin or a benzodiazepine-based drug.

Those days are becoming rarer by the lockdown. It is common knowledge in the medical community that sleep drugs offer little hope for remission. It is also common knowledge that cognitive behavioural therapy tailored for insomnia, called CBTi, has proven to be the most effective treatment option. In fact, in 2019 an AJGP paper recommended CBTi as first-line treatment, with drugs to complement it short term.

So, why aren’t GPs simply recommending CBTi to patients with sleep disorders? The reasons are many fold. Professor Adams, who is looking at how to help GPs increase their awareness of sleep disorders at the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health, distilled it down to the need for a psychologist to be in charge of the six-to-eight week CBTi program.

“If you want CBTi in Australia, you need to be referred to a clinical psychologist to do it, and it costs around $1500 for the full course. To get a Medicare rebate on that you need a mental health care plan. The stigma associated with being labeled with a mental healthcare problem might be a barrier to some patients. Also, many GPs are not aware that you can use the mental health care plan just for insomnia,” Professor Adams said.

“To be fair to GPs,” said Associate Professor Delwyn Bartlett, a psychologist and insomnia specialist at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, “Most doctors, up until recently, would have had somewhere between two and six hours of sleep education in their training. And if they’re in their 50s or 60s, they would have received none. But that’s changing.”

Help is on its way

The Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health is currently trialling an online CBTi program that GPs can refer patients to called Sleepio. Sleepio, like its counterpart Somryst, can be done with or without GP support and has been tested extensively overseas with statistically significant results. Under the institute’s trial, GPs across Australia can start refer patients to Sleepio immediately and they will be reimbursed $50 per eligible patient.

Dr Alex Sweetman, a research associate at the institute, is overseeing the trial, which offers Sleepio to the patient for free.

He said the institute is aiming to recruit 375 patients by trial end.

“GPs have reported a great need for better access to evidence-based CBTi treatment and referral options for insomnia,” Dr Sweetman said. “Referring a patient to a ‘sleep’ psychologist, an online CBTi program, or managing patients with BBTi in the general practice setting are all safer and more effective long-term options than sedative-hypnotic prescriptions.”

BBTi, short for brief behavioural treatment for insomnia, is a shortened version of CBTi packaged for the GP consulting room that Dr Sweetman published about recently in the AJGP. It targets the stimulus control and sleep restriction components of CBTi and has been proven effective for acute and chronic insomnia. The downside is it requires at least six GP appointments and potentially the help of a practice nurse to score a patient’s questionnaire and sleep diary.

Professor Adams suggested much of the BBTi treatment could be managed by a practice nurse.

“The GP could say to a patient, try BBTi with our nurse, who has been schooled up in it, and over the next four to six weeks we can how you’re going. It would also mean psychologists would have more time to focus on complex cases. But how you fund that is something that needs thought, and we’re working on that,” Professor Adams said.

Associate Professor Bartlett trained up practice nurses to lead a CBTi program in a large, rural practice short on psychologists, especially those versed in treating insomnia.

“The nurses were fantastic,” she said. “To make any therapy effective, we need a team approach where all health professionals have a better understanding of sleep in order to intervene before there is chronicity.”

BBTi would effectively be free for the patient, compared to the GBP200 annual charge for Sleepio in the UK. But the cost and time it would take a GP practice to implement BBTi could see it fall by the wayside, unless a GP has a sleep disorder interest.

A free solution for GPs is coming in the way of a publicly available website that will house key resources on sleep disorders and treatments. Working with the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Help, Bond university researchers are currently building the site, which Professor Adams said would be similar in look and feel to the National Asthma Council website. Bond University said it hoped to publish the site before the end of the year.

When CBTi doesn’t help

Research suggests that about 30-40% of people don’t respond to CBTi, according to psychologist Dr Giselle Withers.

“I see many people in my private practice who say that they’ve tried CBTi and it didn’t work for them,” she said. “Some studies have found that people who don’t respond to CBTi continue to have high levels of cognitive arousal, which means they are still worrying and ruminating about sleep after treatment. This is why mindfulness is great approach for people who may not have responded well to CBT, and why adding mindfulness training to CBTi right from the beginning may help a wider range of people, and improve outcomes.

“Mindfulness is much better at reducing rumination and worrying than CBTi, as it teaches people skills of ‘metacognitive shifting’, that is, how to notice thoughts then shift attention back to the here and now. This skill is only assumed in CBT not taught directly. So, if people are not even aware of their thinking patterns, which is not uncommon, then the cognitive therapy component of CBT won’t be effective.”

Professor Delwyn Bartlett said it could also be about getting the timing right.

“If a patient is showing resistance to CBTi or sleeping drugs, the individual may not be in the right space to make difficult changes,” she said.

“I would always give someone the choice of coming back when it is a better time for them to undertake another ‘retraining in sleep’. It has to be about timing. CBTi takes practice and perseverance, and it is not easy.”

Role of mindfulness

Another attempt to make CBTi more palatable is mindfulness behavioural therapy or MBTi. This therapy targets the relaxation training component of CBTi with the hope it will positively affect other aspects of a patient’s recovery. It has shown to be particularly useful in reducing states of hyperarousal.

A Mindful Way is an online MBTi program Dr Giselle Withers developed in her time at the Melbourne Sleep Disorders Centre. It currently appears on the Sleep Health Foundation’s website.

“Mindfulness really helps people to stop putting effort in to get to sleep, which is counterproductive,” Dr Withers said. “It’s about being less judgmental when we’re not sleeping and trusting that sleep will come. It’s also about being in the moment, which helps reduce the anxiety that is perpetuating insomnia. Mindfulness training’s helped patients in many aspects of their lives, because they learn flexibility and how to accept and respond calmly to whatever they’re facing.”

The six-week program costs $247 and is self-paced with 15 to 30 minutes of daily meditation as a foundation. Monash researchers recently put the program through a pilot randomised control trial and found nine of 12 participants who undertook the MBTi program achieved remission. The paper will be published in an upcoming volume of Mindfulness.

The newcomer

Sleep practitioners and researchers are also keeping an open mind on cannabinoid (CBD) oil, which is proving to help acute and chronic insomnia patients minimise intermittent waking in the night. Dr Banerjee is a strong advocate, and has even given himself the title “Sleep and Cannabinoid Physician”.

“We find CBD oil is effective for improving sleep disturbance and the other symptoms of anxiety, such as headaches, teeth clenching, palpitations,” Dr Banerjee said.

“In reality sleep is so disturbed for some of my patients that despite CBTi, the insomnia is quite rampant. Medication is the way forward when they are at this stage, in addition to CBTi.

“If insomnia is driven by depression, then CBD oil will not be as effective, unless there is a large component of anxiety mixed in with depression. I have been having success using CBD oil to wean patients off benzodiazepines and other psychiatric drugs used at night, such as seroquel,” he said.

Professor Ron Grunstein, a professor in sleep medicine at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, has looked at the CBD data and is not yet convinced.

“I don’t think there’s strong evidence because studies have been fairly small, but the quality of medical literature is improving,” he said. “The problem is every man and his dog has access to CBD oil and there are companies and doctors everywhere wanting to cut corners.”

Professor Grunstein said he would keep a close eye on CBD oil. When asked what the best drug choice was for chronic insomnia patients who have shown resistance to CBTi, he labelled suvorexant and related drugs the medication of the future, despite the exorbitant cost.

“You need to use suvorexants for at least one to two months, and there’s sufficient data on usage up to a year,” he said.

Is there an app for it?

Professor Grunstein is also involved in the development of an app, Sleepfix, that targets the bedtime restriction component of CBTi. The app is recognition that many people with insomnia spend far too much time in bed attempting to sleep.

“There is evidence that limiting bedtime at first and then gradually increasing it is an effective behavioural treatment for insomnia,” Professor Grunstein said. “What we call sleep re-training is known as the most effective form of behavioural therapy.”

With the ability to connect to a FitBit or activity monitor, the app will provide a person with detailed information about their sleep and sleep attempts. It is currently being tested with online digital health company, MOSH, and in the Woolcock clinic. Professor Grunstein said the intention was make the app permanently available on platforms like MOSH.

“Particularly at times like this, digital health is very helpful in terms of getting people access to healthcare,” he said.

*Name changed for privacy.