What happens if government puts a stake in the ground, as has occurred in the US and the UK, and says to local providers and vendors, enough is enough, you’ve all got five years to be open and interoperable to this standard?

Interoperability is a dirty word.

It promised us so much but has disappointed us so much more.

It dictates nearly all of our serious thinking time in digital health. We are obsessed with the word, with the problem.

It drains away enormous amounts of funding in all sorts of ways which somehow are never in any meaningful alignment.

Free One Day Webinar on this and related topics, Tuesday August 10, Register HERE

If you look at the interoperability scoreboard in the last two decades, you don’t see many wins: perhaps electronic prescribing is a notable recent exception, although this is still not working properly.

In the context of our current digital health infrastructure, it has been significant. That context is that we really don’t have a digital health infrastructure as such.

What we have is a fragmented melange of one government moonshot (now lost in space), several secure messaging dead ends, state government ‘not invented here’ bespoke solutions, , most focussed at the tertiary sector, and a primary care sector stranded in legacy land.

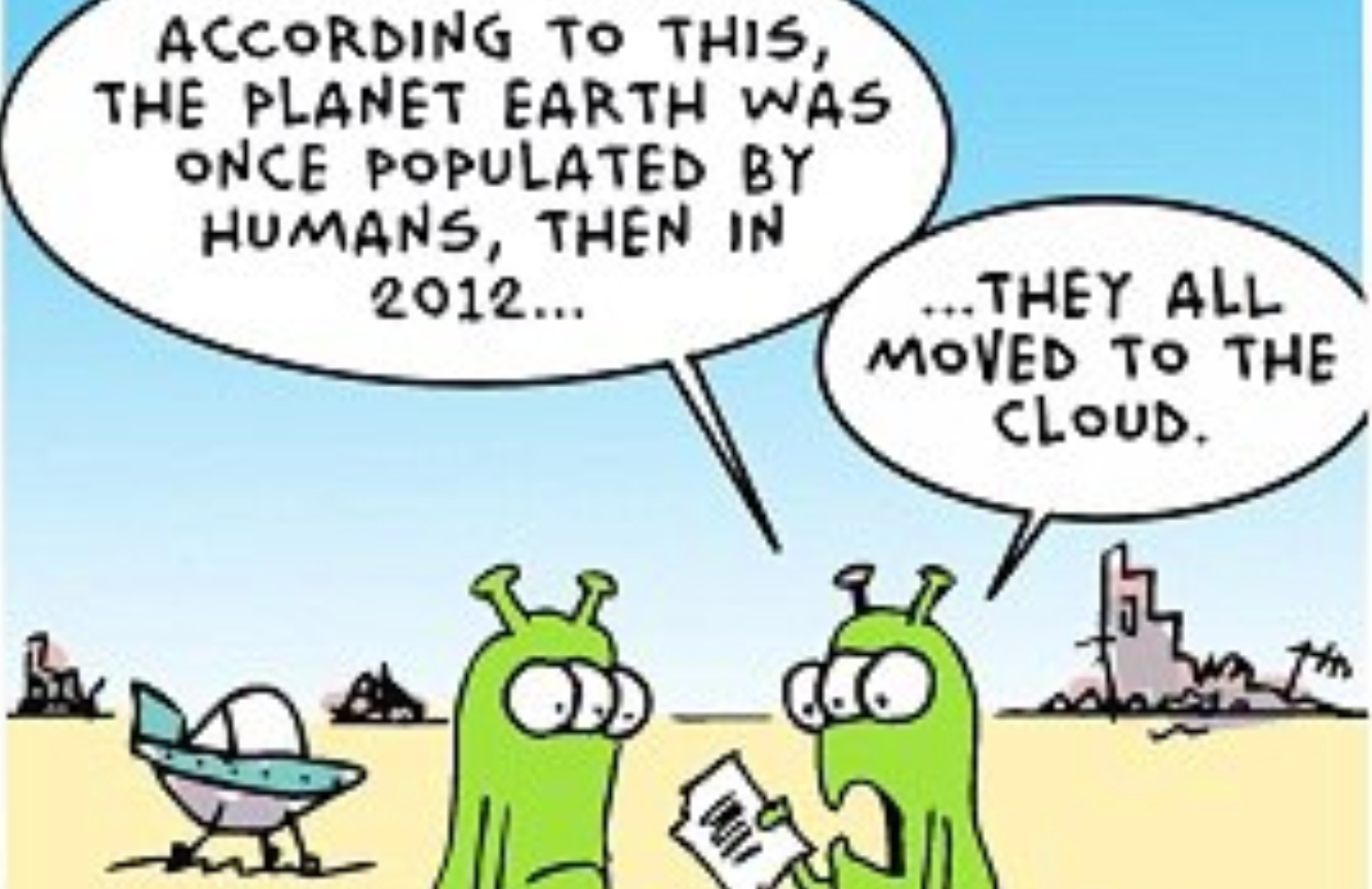

Alongside we have a selection of innovative private sector cloud players, who all struggle because they don’t have a strategic framework or any meaningful common infrastructure to work with.

The result is an ever increasing range of solutions, some connected to each other in fenced ecosystems, most not connected to much meaningfully, and virtually none with commonality in communications protocols.

We have too many moving parts, and little co-ordination between governments in a federated and divided system.

We have a large and growing legacy of server bound systems which isn’t being meaningfully challenged because there are no funding signals to incentivise a proper challenge. And we keep adding to the legacy because legacy is the only infrastructure we have to work with.

We have a set of funding models designed in the 70s and the 80s, which don’t address an obvious need to incentivise the enormous utility of the web sharing technologies ,which are revolutionising other sectors such as banking and finance.

We have a complex and interwoven base of incumbent vendors and providers who all make money today on legacy products and aren’t being sent any meaningful signals to change their ways, so they don’t.

We do have a small set of disruptor vendors (some with money laden backers) determined to crack the future, with or without any base infrastructure by using the cloud. Which in this set up mostly adds to the complexity and confusion.

Finally, apparently, 72% of the public, think we have a great healthcare system (Source: Australia Talks, 2021, ABC). And today, in relative terms to places like the US and the UK, we do.

There is no burning platform for politicians to stick heads above the parapet, read the tea leaves, and take the risk of initiating significant and meaningful change to this set up.

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”.

Is there a circuit breaker on this slow boiling monster frog?

Perhaps.

What happens if the federal government puts a big stake in the ground, like its counterparts have the US and the UK, and says to local providers and vendors: “enough is enough, you’ve all got five years to be open and interoperable to this standard, or you can’t participate in the system”?

And then: “We know this is going cause a lot of you short term pain, so we have good plans in place to help you wherever it makes sense”.

A really honest statement on the part of government would add:“…but let’s face it, on the other side of this, some of you won’t be here anymore”. But it’s probably not necessary, because most vendors and providers already understand this. It’s been part of the problem.

Let’s first look at the upside of such a move on the part of the government:

- So long as you pick the right parties to provide assistance to through the transition and play the politics well, you aren’t really even sticking your neck out that much in political terms. The vendor community has virtually no political clout, although of late they do have influence in Canberra. But political clout and influence aren’t the same thing. Providers are another problem altogether. Getting on the wrong side of the AMA or the Pharmacy Guild can be a risky political game. But outside of private healthcare and insurance, you control the all purse strings anyway, so with the right plan, and partners, the political dimension should be manageable (actually, to all intents you control the purse strings of private providers and health insurers as well, so all good).

- It’s the biggest stake in the ground since the PCEHR (now the My Health Record), but this time, you already have a lot of backers for the idea, the idea has been successfully implemented overseas, and, the idea makes almost complete sense. The My Health Record started as a political thought bubble and had many detractors from the outset (as it should have had). This move stands a good chance of being perceived by many players as strong leadership (not all players of course as not everyone wins if you force change like this, most of all incumbent vendors).

- If it works, whoever actually puts the stake in the ground might eventually be famous.

- It’s not going to cost much. Maybe $5m-$8m per year for each of the first five years to build a rigorous and effective standards organisation and adjacent services to manage the whole process. When you compare that to $1b for the first five years of the My Health Record, it sounds like outrageously high return for relatively low risk.

- It’s what government is supposed to do: facilitate change through effective governance when the private sector is stuck in the mud.

- You aren’t building and then trying to maintain a giant piece of infrastructure. You are building an agile and innovative organisation that will create and maintain an innovative framework which industry can work off and work with.

- The whole thing provides the basis for a strategic framework for the alignment of all of healthcare. You don’t even need to publish a 300 page five year plan for everyone every few years. The plan is simple: everyone has to enable their institution to talk as seamlessly as feasible to everyone else. And to do that technology and vendors will need to fall into line. Much of the rest will take care of itself.

- The alignment moves the whole system to transformational web sharing technologies: transformational for vendors and providers, but most importantly, transformational for patients. Open web based sharing platforms will among all other things make data significantly more accessible and usable by patients. It might be the first time ever that the term patient centric is deployed with any real intent and meaning.

- With a government mandated framework for the future of digital health, private investment will have certainty to work with and the confidence to invest a lot more into the system. It should be a virtuous circle if it works.

- Aged Care and Mental Health have been allocated well over $20 billion over the next four years by happy circumstance (our 2021 federal budget). So there is plenty of public money available in the system to grease the wheels of this major change.

- It’s a project that can easily run parallel with our continuing fetish to maintain and redevelop the My Health Record. Over time it might give the government and the Australian Digital Health Agency enough success, momentum and kudos to start re-examining the fetish, and letting it go a bit.

What could go wrong?

As things go, a lot.

NEHTA, the PCEHR and the MHR were all developed ,run and fought for, by good people with good intent. And a lot went wrong.

Standards by themselves aren’t a magic bullet.

Standards regimes can retard innovation as much as they can promote it, if managed, funded and deployed in the wrong way. There is a lot of room for error, especially in a federated system where federal and state governments pretend to play well together but don’t when it suits them.

Governments will need to surround any standards and related working frameworks with carefully calculated support, to the right providers and vendors, at the right time.

A cloud based interoperable healthcare sector will work very differently from the one we have now.

Not only will there be a set of losers who will make every attempt at derailment of this change, but the new models that emerge from this new way of working together will not likely be sustainable in the long term if there isn’t some parallel and meaningful work done on our funding models.

Unfortunately, at this point of time it’s going to be very hard to second guess just what new business models might evolve, and how the funding regime could be altered to support them. There is a big degree of unknown in moving to this future.

There will likely be platform based businesses where data transactions will be centralised and concentrated. Some providers will become important nodes and dominant. Others will disappear.

While we know providing healthcare will be changed substantively to be more efficient and more patient facing, the economics of cloud based providers and businesses are wildly hard to predict.

There will be unknown unknowns.

Who is going to pay who for what in this new interoperability paradigm of the cloud is undoubtably the biggest challenge of undertaking the change.

Losers, some likely with political leverage, will emerge along the way.

A simple but important example of business and funding model change that might occur in cloud transformation relates to the data which such a new paradigm will generate for government and providers. Detail on the longitudinal journey of patients into chronic care, into and out of hospital care, and eventually into aged care, will make it entirely feasible to fund lots of providers for outcomes, not for sessions and procedures. That isn’t what Medicare does today. And its of intense interest to a politically powerful but troubled private health insurance lobby.

This is a funding journey that eventually will be fraught with difficulty for any incumbent government.

But if we succeed in obtaining meaningful interoperability in our healthcare system by putting this stake in the ground now, the change, challenge and disruption will almost certainly be transformational for the efficiency and utility of the system. And more than ever before the transformation will likely empower patients in the value chain of healthcare delivery to a degree they’ve never been empowered before.

Who wouldn’t press the button today on such a journey?

If you’re interested in the topics raised in this article check out the Agenda on our upcoming Inaugural Cloud Healthcare Summit on August 10 HERE. Registration for the live streaming webinar is free. Other enquiries can be put to our producer Talia at talia@widlhealth.net.au.