A 17-year-old boy presented to his GP following months of increasing medial knee pain and swelling.

There was no antecedent traumatic event, but there was a history of recent increase in intense exercise on hard surfaces which was thought to be contributing to the presentation.

There was also possible weight loss, although the recent exercise clouded the issue.

On examination, there were clinical features suggesting a medial meniscal tear, with pain and swelling at and below the medial joint line.

The patient was treated with anti-inflammatories and was asked to follow-up with the GP and undergo MRI scanning if the symptoms had not resolved within 10 days. Unfortunately, no clinical follow-up or imaging was performed until almost three months following this initial presentation.

Image findings

First-line imaging given the clinical suspicion for a meniscal injury included MRI of the knee, which demonstrated a large osseous lesion in the proximal lateral tibial metaphysis, with associated bony destruction and an enhancing soft tissue mass. There was no intra-articular extension or pathological fracture.

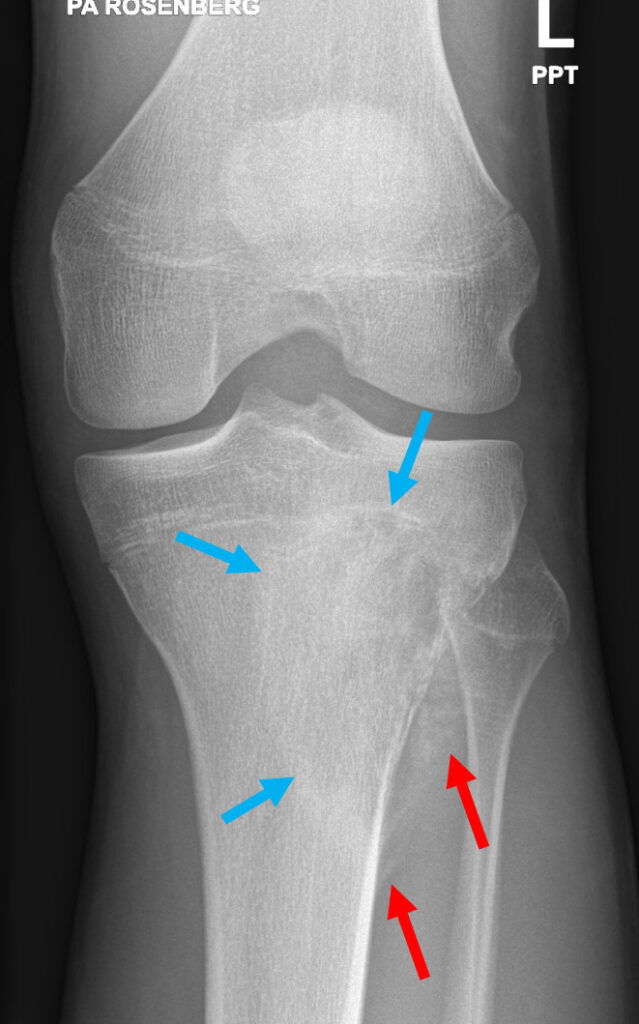

A radiograph of the knee performed concurrently demonstrated further features of bone lysis, poor zone of transition (i.e. ill-defined margins), periosteal reaction (Codman’s triangle), and a soft tissue mass with ossific calcified matrix.

The imaging features are of a rapidly growing aggressive bony lesion, and with the presence of an ossified matrix, an osteosarcoma was diagnosed.

Consequently the patient underwent further imaging staging and urgent referral to a bone tumour specialist.

Analysis

This case highlights the different strengths and weaknesses of various imaging techniques. MRI is best in this setting in delineating the extent of tumour spread and assessing a soft tissue mass, evaluate the degree of aggressivity, as well as judging treatment response. However, MRI typically struggles with characterising the nature/cell type of bony tumour and should ideally be interpreted in conjunction with X-rays. MRI can sometimes assist in characterising the nature of the lesion in specific instances such as cystic lesions or non-mineralised tumours.

Radiographs on the other hand are useful in assessing tumour matrix. This indicates the type (if any) of calcification produced by the tumour, be it cartilage versus osseous. Osteosarcomas typically produce osseous matrix.

Radiographs also can help to characterise periosteal reaction. In this case, the periosteum is lifted up in a triangle (Codman’s triangle) due to new subperiosteal bone forming when a rapidly growing lesion such as a tumour lifts the periosteum away from the bone at the advancing margin of the lesion. The periosteum does not have time to ossify except at the leading edge.

The age and location of the tumour contributes also to bone tumour diagnosis, as certain tumours typically affect a specific demographic and anatomical location.

In summary, imaging workup of bony lesions is best performed with a combination of radiographs (and/or CT) and MRI.

Dr Sebastian Fung is a musculoskeletal radiologist who undertook an MRI imaging fellowship in Hospital for Special Surgery in New York. He now works in Sydney at St Vincent’s Private Hospital and Mater Hospital.