Radiotherapy machines do not come in travel-light sizes, I realise, on seeing the prototype Nano-X machine, the brainchild of the University of Sydney’s ACRF Image X Institute.

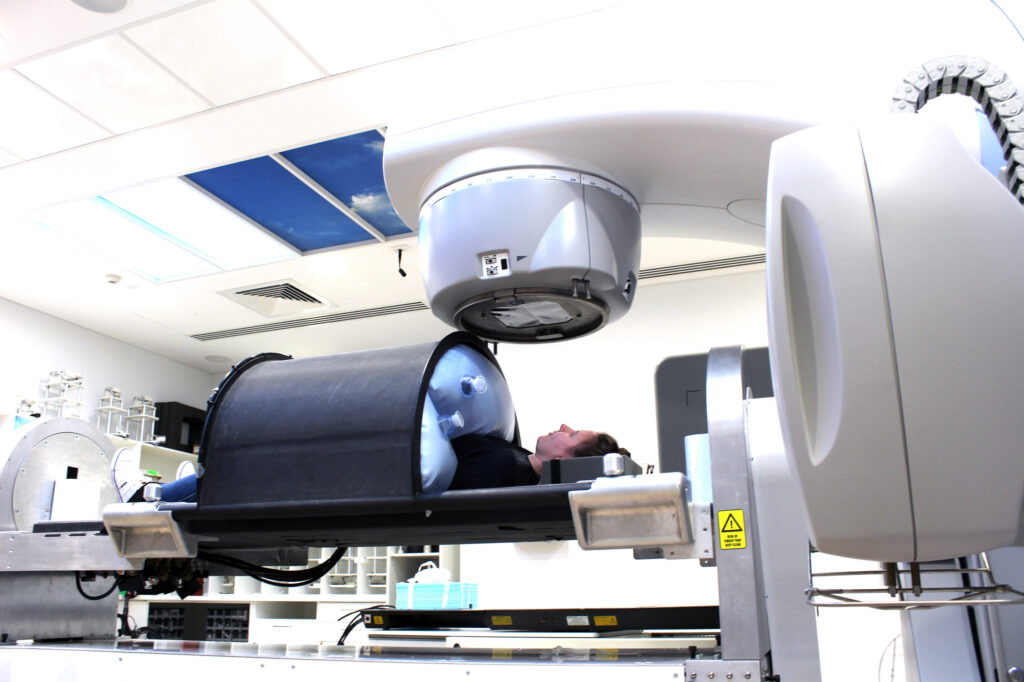

But size can be misleading. What’s different about this machine is its radiation beam. It remains fixed while the patient spins, the opposite of what a LINAC machine does. The Nano-X’s beam travels from its bulbous shower-head-looking top directly to the floor, a redesign motivated by affordability.

“We think it will reduce costs of owning a machine by two-thirds,” says Dr Mark Gardner, research associate at the ACRF.

It has huge potential. One in two cancer patients worldwide need radiotherapy but less than a third get access because of the prohibitive expense of a LINAC. The Nano-X could be the answer cancer communities in the developing world have been waiting for.

You do not need as big a room to house it, and you do not need to shield the room against radiation bouncing around from a rotating beam. The institute has also designed operating software that lowers the staff-to-patient ratio required.

The Nano-X has been tested on plastic humans and even a frozen turkey. A patient trial is under way at the Prince of Wales Hospital to see if patients can withstand being turned like a pig on a spit, and another trial will start in July 2021 to see if imaging quality taken from a rotating patient is up to scratch.

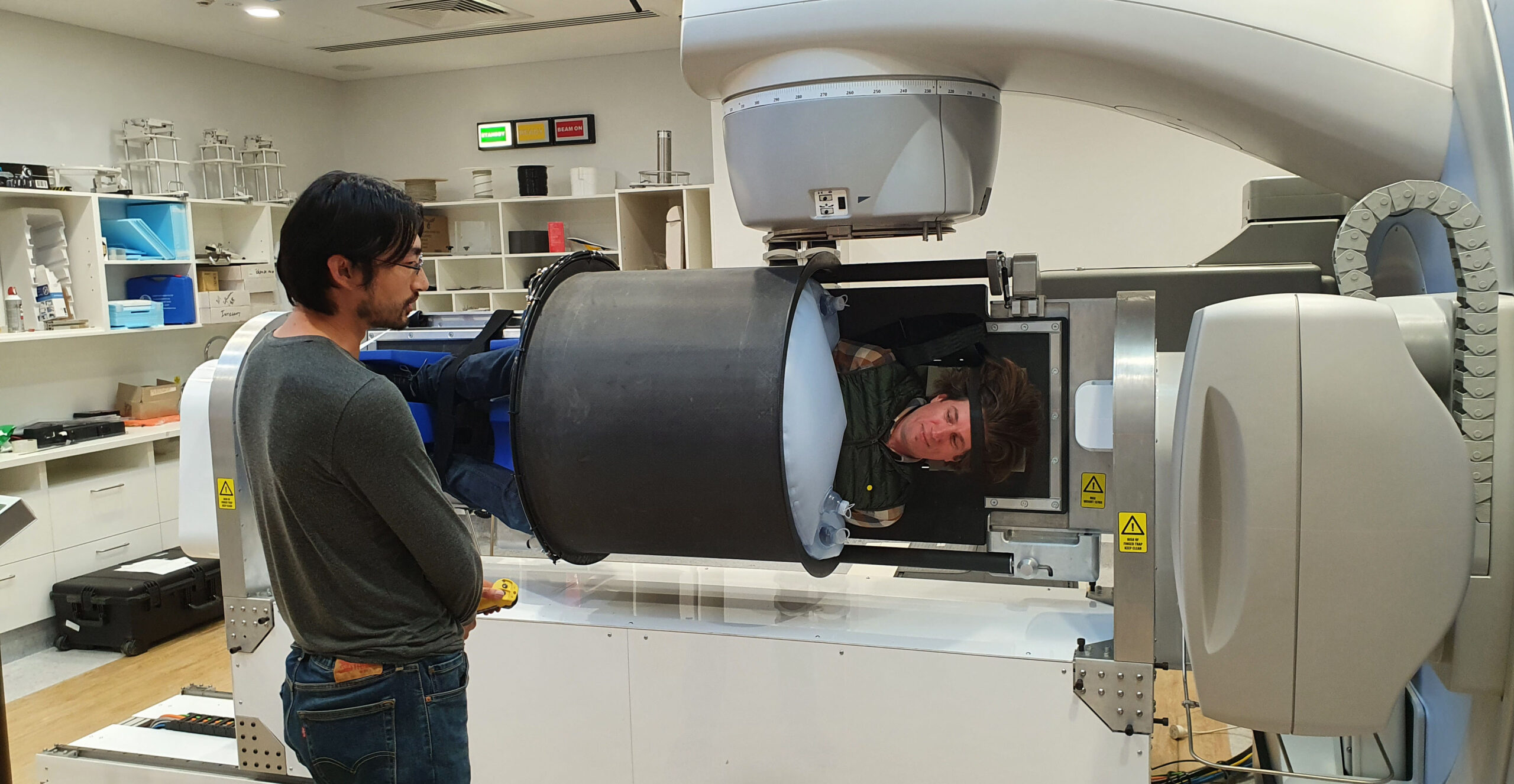

I decide to hop in for a spin, literally. Research associate Dr Paul Liu closes a sun-tanning-looking lid over my chest and upper legs, and begins inflating the bags on the lid’s underside. The pressure mounts on my clothes but it never becomes uncomfortable, more like a very tight hug. The carbon fibre bench I’m lying on moves into position and Dr Liu turns me 90 degrees and holds me there.

“We envisage a patient will be spun fully for the imaging, and then four to five times to suspended positions like this one for the treatment,” Dr Liu says.

We complete a full spin at slow speed, 12 degrees per second, and my only concern is slipping, but the lid and straps hold me tight. Otherwise, the sensation is almost calming. Once the imaging trial is completed mid-2022, an industry partner will be engaged to build a market-ready model.

The Image X Institute knows a thing or two about radiotherapy machines. Most lung cancer patients treated with radiotherapy around the world are imaged with a respiratory CT method pioneered by the institute’s director, Professor Paul Keall.

A more recent institute solution uses an algorithm on patented technology to make the imaging machine rotate in time with a patient’s breathing, a feature particularly helpful for lung cancer patients.

“If the patient breathes faster, then the machine moves faster, and vice versa,” says Professor Ricky O’Brien, deputy director of the ACRF.

This seemingly simple solution is a world first, improving imaging quality, reducing imaging time from four minutes to one, and reducing radiation by more than 15%. Clinical results will be published soon.

“The key challenge we face is that tumours move because people’s bodies move,” says Professor Keall. “We can beam large enough areas to encompass that tumour but that means the patient gets extra radiation. So, we come up with devices and algorithms to make technology smarter.”

Another institute solution, called KIM, allows the patient to be imaged during treatment and tells the treatment team if the tumour target has moved away from the beam, helping to avoid healthy tissue.

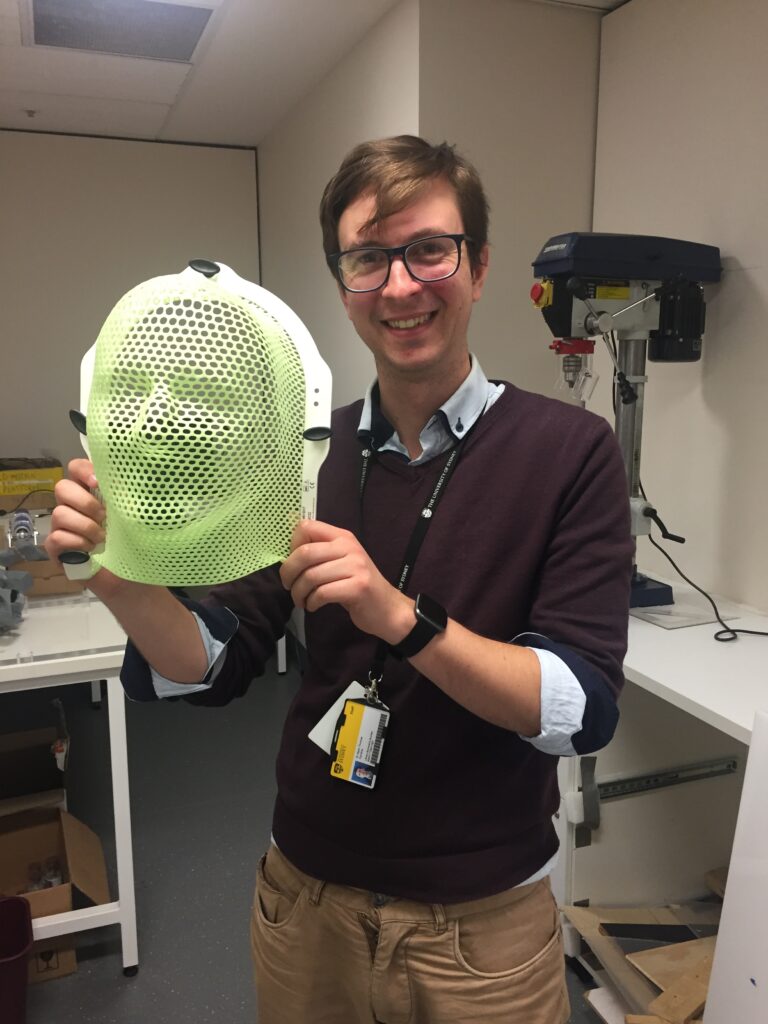

An earlier-stage project is Remove the Mask. Media personality Julie McCrossin, a head and neck cancer survivor, has raised awareness of the stressful time patients face being bolted in by the lime-green mesh-looking mask for up to 45 minutes every treatment. Anxiety and claustrophobia are common.

Dr Gardner and fellow research associate Dr Youssef Ben Bouchta are investigating if they can move the beam in response to the head moving, making the mask redundant. Dr Gardner is working on algorithms to make existing technology smarter while Dr Bouchta is creating a hardware solution. A better patient experience is the end game, with a clinical trial forecast for 2024.

When an idea is clinically proven, the Image X Institute has the commercial links to capitalise on it, thanks in part to Professor Keall’s time in the US, working at Stanford University. Three start-up companies and eighth commercial licences are proof in the pudding.

“When you build up a lot of successes, people begin to trust you,” Professor Keall says.