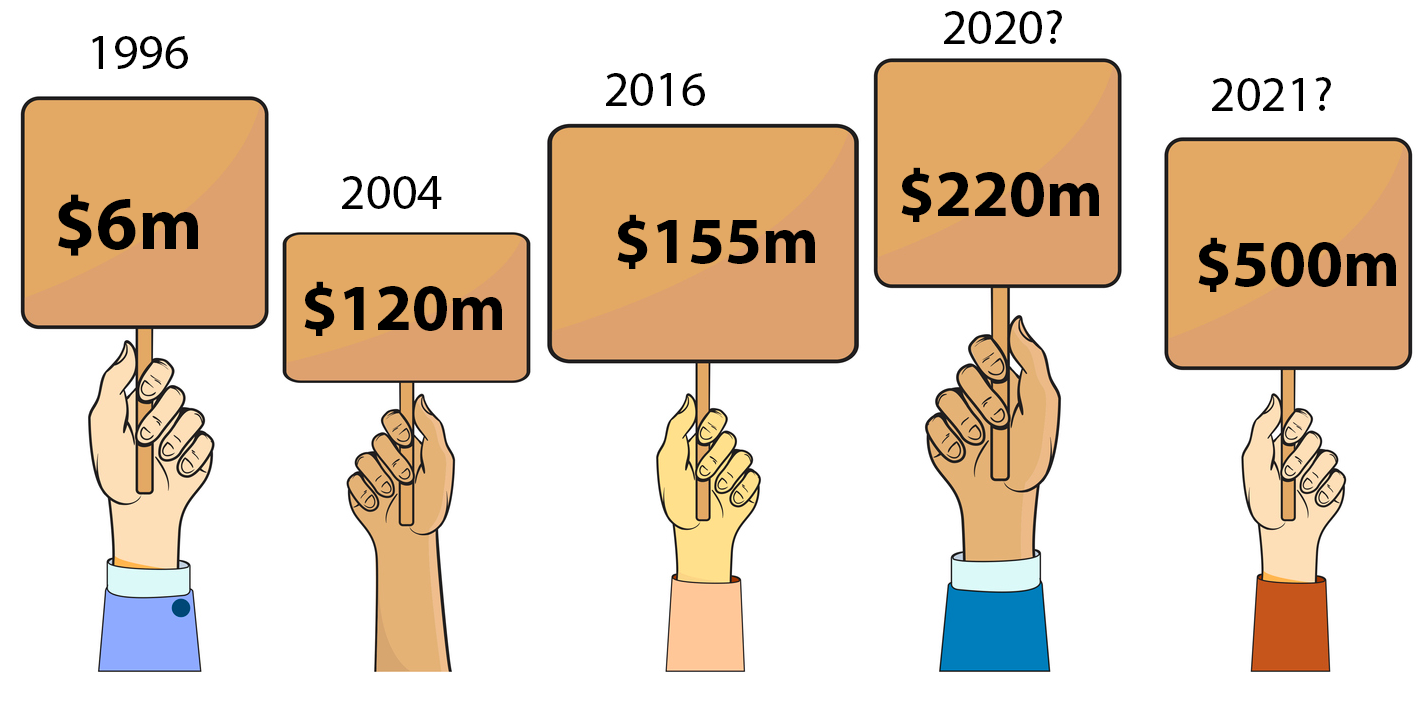

I’ve written numerous stories over the years about how much Medical Director (MD), one of our two largest GP patient management vendors, is worth, and more recently about what it might mean if it was sold to Telstra Health, as strong rumours suggest.

In my recent calculation (Our 11 most valuable digital health companies) , Medical Director is worth about $220 million.

Wrong… apparently (it occurs quite a bit that I’m wrong as things go).

According to insiders at the Australian Financial Review this week, the going price for the company is going to be about $500 million, and Telstra Health, as previously reported by The Medical Republic, is the front runner in an auction that is due to end early next month.

$500 million?

That would make Frank and Lorraine Pyefinch, and Sonic Healthcare (the major shareholders of Best Practice (BP)), pretty happy I’d imagine, because based on that valuation, BP is worth at least $650 million and possibly up to $1 billion. This is based on it having a much better share of market of GPs, it still gaining share of market based on price and product, over MD, and a few other less well-known factors such as where it is in the development of its cloud version of its product offering.

When I wrote that article and did those valuations, I got a few calls from some of those vendors, who suggested I had under-priced them by quite a bit. I didn’t get a call from Medical Director (I rarely do, because of articles like this I guess), but I did from some market analysts who’d suggested I had over-priced them by quite a bit.

Far be it for me to question long-time financial analysts, who are qualified in the art of valuation, and who work for highly respected institutions such as Bank of America, which is advising Telstra on the sale.

But I will give it go.

Since its sale to private equity group Affinity more than five years ago for $140 million (notably Telstra was interested back then as well), MD has:

- Lost significant amounts of market share in the valuable GP market to BP. Accurate share figures over the years have been impossible to obtain (hopefully those doing the due diligence have their head around this issue) but when Affinity acquired the business five years ago it was generally thought that Best Practice was maybe a little behind in share from MD but catching fast, with each having about 42% each of the market, but now estimates range from 30/55 to 38/47 for MD/BP. That’s a lot of share loss.

- MD has increased both its revenue and profit in that time, which makes sense only if it has put its price up a lot, which it has. So MD is a lot more expensive than BP in most comparisons.

- Anecdotally, BP is a far more loved and trusted brand in the market these days.

- Helix, the cloud version of MD and which was the great marketing hope for MD, has failed to get any traction in the market. Hardly any GP practices use it. This might have been explained away as Helix being ahead of its time, but it doesn’t explain why the other two major cloud vendors, Clinic to Cloud and MediRecords, have managed in one way or another to secure contracts for huge numbers of users, albeit outside of the small to medium GP market, and Helix has failed.

- Note: I am a non-executive director of MediRecords and that prevents me from revealing a few things about that business, but what I can say is that while it has failed to get traction in the GP market as a cloud product, like Helix has failed, it has managed to secure some very large and interesting enterprise contracts that would not have been possible without the product being an agile and scalable patient-management enterprise solution. It beat Helix and MD to these contracts in one way or another.

- Employees who have left MD over the years haven’t been particularly complementary about how it was run, how it treated its customers, and about Helix, which some have claimed was never built as a cloud version of MD but was developed as solution for the bulk-billing model of past owner Primary Healthcare, that could never be adapted properly to being an all-purpose cloud-based ambulatory patient-management solution. I will emphasise here that these are all stories told by ex-employees, and that doesn’t necessarily mean these stories are true. But it doesn’t feel great.

Last but not least in the issues facing a valuation of $500 million is that MD is facing off against the greatest challenge in its commercial history: the rapid advance of disruptive open API, cloud-based solutions to healthcare interoperability.

Nearly all of MD’s revenue and installations are based on old server-bound software technology.

There is some irony here in that the managing director of MD (the MD of MD), Matthew Bardsley, is a cloud zealot. He believes entirely and preaches the future of interoperability in health via the cloud, and in disruptive healthcare business models.

But the vast majority of his company’s installed product base and revenue base is legacy. It, along with a lot of other Australian medical software vendors today, probably including its main competitor, Best Practice, have a giant technology debt.

Such technology debt can be overcome. And if you’re going to do it, the best place to do it from is a position of significant market leadership. While MD isn’t the market leader, it has got significant market share and there is daylight until number three in the market. BP and MD dominate.

But there are huge risks to such technology debt for a buyer. The obvious one is the vast sums of money needed to reinvest in overcoming the debt. If you pay $500 million for MD, you are going to need to pay something like another $50-$100 million to get yourself over your legacy technology position and transitioning your product suite to cloud without destroying your revenue base, as cloud is a different proposition in financial terms for buyers of a patient management system.

In the case of Telstra Health, this probably won’t be a problem. They have tonnes of capital.

The problem more likely is that with highly interoperable cloud-based technologies not quite at a tipping point in the Australian healthcare system, no one could really have confidence that the business model of these major PMS software vendors which is based currently on older server base products will transition easily to a cloud ecosystem.

If you’re a betting person (I always admit I am in moderation), if you have money, a very dominant market position and smarts, you are likely to make it to the other side, so this augurs well for both BP and MD. But it’s not going to happen without a fair bit of blood, sweat and tears, a lot of capital and a fair bit of risk.

Which I would have thought made $500 million look like a high price.

So what might behind a preparedness to outlay so much money on something that looks a little tired, over leveraged (a lot of cost has been removed from the business) and risky? (OK, that’s a little rough, MD makes a lot, has good market share, and is surely worth something like $200 million or more, which is quite a lot so it’s not a terrible business).

Here are three ideas:

- General practice is the most important transactional data point in our healthcare system now, and in the future this position will be amplified substantively as the need to optimise interoperability in patient data between GPs, allied providers, specialists, hospitals and the patients themselves, becomes the secret to system efficiency, security and safety. The GP node is the gatekeeper data position now in the future

- An open operating system, API, cloud world, tends to be a “winner takes all” world. It’s a world where once you have a platform that is used the most, network effects of users and data tend to reinforce one platform. This is why we have Amazon in retail, Facebook in social media, Google in search, Apple in consumer applications access and Microsoft in business apps, and its hard to name who is their main competition. In a cloud world, users reinforce the value of a platform to the point where there are usually few if any No 2s and if you’re number one, the world of opportunity to make money in all sorts of new ways tends to open up. You own distribution. And that means you can charge everyone who wants access, If Telstra buys MD, it must have this in the back of its mind for Australian healthcare, and if this reasoning for valuation turns out to be true, $500 million might end up looking like a bargain.

- The Department of Health looks set to introduce some firm deadlines for healthcare providers and vendors to transition everything they do to the far more interoperable world of the cloud. If we are going to use the UK and the US as examples of how long that timeframe might be, it’s likely about five years’. In the same period, the federal government has said it will spend at least $17 billion on aged care and to do that it knows that it has to digitise the aged care sector and connect it to the rest of the healthcare sector, mainly general practice. The enterprise contracts to make aged care interoperable in healthcare over the next few years are likely to be very lucrative and Telstra Health already has large positions in aged care digital solutions, as well as in other parts of the healthcare delivery chain, notably pharmacy and medication management. With MD as a part of its portfolio, technology-debt-ridden or not, Telstra would have a lot of the chips needed to win a lot of these contracts and to start connecting various parts of the system.

So perhaps $500 million is not so outrageous after all.

For GPs, both the price Telstra Health is prepared to pay, and that Telstra Health might own it, could hardly be bad, even if Telstra has in mind the “rule the world” platform aspirations within Australian healthcare that the global digital platforms have.

Apart from anything else, it will put a rocket under BP and Sonic to get on with the development of its cloud product, and alongside BP, most of the local medical software industry, legacy vendors and entrepreneurial new entries alike, will all probably be more valuable, and as a result be able to access funds to make the whole process of innovation go a lot faster.

Combined with the federal government’s determination to introduce a regime where providers and vendors will be forced in some way to move to far more interoperable cloud technology within about five years, the sale of MD to Telstra Health could constitute the starting gun on a whole new era of innovation in Australian healthcare.

Much of that innovation will be aimed at the gatekeepers of the most important information transactions in health moving forward: general practitioners.