22 July 2021

Medicine Unmade: so starts general practice’s most disruptive decade

In 2006 I employed a youngish English upstart to run one of our most distressed divisions at what was once Australia’s largest business publisher.

We had much bigger and more promising divisions at the time, one a wildly growing internet business directory start-up that was going global, another was our healthcare division with its flagship title, Australian Doctor.

The media group was an afterthought by that time. It had been in decline for some years, and this was even before the most destructive forces of traditional media companies – Google, Facebook, Twitter and co – had barely got into first gear. Tim, who by coincidence had once been editor of Hospital Doctor in the UK, loved the cut, thrust and the schlock of the advertising and media sector. He was also ambitious, smart and tossy enough to take the odd crazy risk.

In 2008, two years to the exact date I had employed Tim, he walked up to my desk, smiled and handed me his resignation, citing a conversation I didn’t remember having on his first day, when apparently he said to me very clearly he’d be staying for only two years.

In the two years Tim worked for us, he hadn’t exactly turned the media group into a raging success, but he had revitalised the division enough for us to start wondering whether there might be life in it yet.

We needn’t have bothered wondering.

Tim left to start a digital-only media group with an English friend, who had also worked for us in our travel division, and within two years it was apparent that his digital-only group, started with a $300-a-year WordPress blog, was going to all but wipe out the three existing business-to-business players in the media market. We owned one of them.

He and his then colleague, Martin, built a business four-and-a-half times the size of our media group in just nine years. But that wasn’t the spectacular bit. What was amazing was that they built the group through the most disruptive and carnage-ridden period for traditional media in history. In the decade they started and grew, the new digital platforms laid waste to newspapers, most B2B media, magazines and even to a large degree TV and radio.

Reed Business Information, by that time called Cirrus Media and run by private equity, sold its media division in 2014 (I had left a month or so before this sale, if you want to work that one out).

In 2017, Tim and Martin sold their business – Mumbrella, if you haven’t already guessed – for what I calculate to be more than 20 times as much.

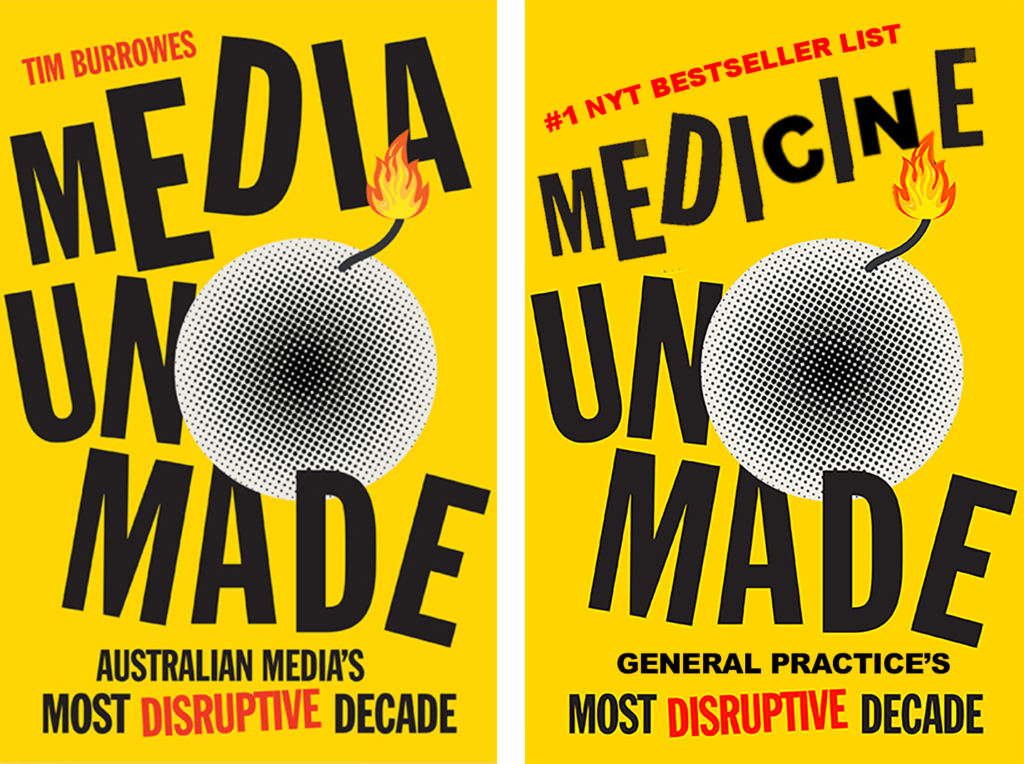

Tim stayed on with the group after the sale and while working as an “editor-at-large” (media-speak for hanging around doing pretty much what you like as a sort of brand ambassador) managed to write a book about the past decade in media. The book was published last week and is called Media Unmade: Australian Media’s Most Disruptive Decade.

Tim then resigned from Mumbrella with a sort of “my work is done here” series of interviews, declaring he hadn’t worked out what he was going to do next.

Sure.

People who work in medicine like to think that medicine is very different from all those other sectors such as media, which have undergone radical transformation, triggered largely though the rise of the global mega digital platforms and digital technologies.

This is in large part because, until now, medicine has stubbornly resisted the mysterious and at times disturbing forces of “digital transformation”.

But there’s a storm coming now.

Medicine has resisted change where other markets haven’t in large part because it is a massively complex information market, with no global standards to speak of, but with more governance and regulation by government than any other sector due to it being so important to the citizenry of a country, and, so expensive to maintain (Healthcare is by far the largest component of any developed country’s national budget).

A country that hasn’t got its health system in shape is a country that is bound for political trouble, so politics loom large in all of the above. And this hasn’t helped either. Change in health is a very-high-stakes game for so many players, and the tendency has been for all parts of the system to resist change.

The stakes are especially high for medical professionals because, until now, the system has protected their ownership of life and death information. Governments have granted the medical profession exclusive licence to wield the power in what until now has been a hugely asymmetric information relationship with patients. If this relationship evens out a lot over the coming years, what will happen to the profession of being a doctor is an understandably worrying question.

It is apparent now that there are significant cracks starting to appear in the traditional way we have looked at medicine, how we have run it, and how we have funded it.

The biggest cracks are being prised open by digital technologies.

Biotech is also starting to turn some parts of medicine upside down but digital technology is going to have the most transformational impact because digital health is making the sharing of secure data between providers of healthcare and their patients so much easier. This is ultimately about patient empowerment, a buzz topic that has seen a lot of promises and good intentions over the past decade, but very little in the way of meaningful progress.

The system has a lot of rusted-on components. There is a lot of money and careers tied up in the status quo. This is especially so among a maze of long-term technology vendors whose bread and butter has been based on owning patient data, or at least, making it very hard for that patient data to leave their commercial sphere of influence.

Various parties who you might have witnessed evangelising the idea of patient empowerment and seamless data sharing across the healthcare system, are understandably quite nervous behind the scenes of what might be on the other side of such potentially disruptive change.

In our current system we have so many legacy settings and set-ups that have to get from one side of the opportunity of digital transformation in medicine to other that there unquestionably be many casualties in the change. There hasn’t been any market where digital transformation has taken hold and not seen losers. It is a scary proposition for many.

Our legacy settings are starting to strain significantly now, and almost certainly, some are going to start to give in the near future.

Some are even going to be deliberately moved on by government.

The momentum for change by our federal government via the utility of cloud technology has gathered significant pace in just the past couple of years. Canberra is embracing the cloud and some state governments are deploying customer-facing cloud services that are revolutionary compared to what went before.

Not long ago, I used to think you couldn’t look to other markets that have been transformed digitally and make comparisons to medicine because of the complexity and governance in this sector. But when I read Media Unmade this week, I felt a lot of pretty creepy deja vu about where medicine is today and where publishing was back in 2008.

There are some significant parallels now that bear thinking about.

But just in case you are feeling like this op-ed is moving the way of a doom and gloom and you can’t keep reading, you can. It’s scary but at the same time exciting. And it is inevitable.

Also, there is one very significant difference for GPs between what happened to media all those years ago and what is happening to medicine today, from which GPs can take heart.

In media disruption, government and society came to the conclusion that journalists and journalism were an acceptable casualty of change. When those 3,000 journalists lost their job in one week in 2012 between Fairfax and News Corp, there was a little shock around the place, but not so much that it was horror that things were breaking down unacceptably.

That isn’t ever going to happen to the GP profession or medicine.

As things stand today, we need a lot more GPs moving into a future that will be dominated by chronic care. The GP network, if we can make it connected with the rest of medicine – with hospitals, allied health and community – are the secret to the management of chronic care, and managing system costs into the future.

Phew.

GPs are OK. In fact, they’re going to be needed more than ever.

But what about practice owners and the traditional general practice model the way it mostly operates in our community today?

The idea that the traditional general practice model of an independent community-based GP group – large or small – can keep swimming merrily along with what is coming – not that anyone thinks it’s swimming particularly merrily at this point – is an idea that is almost certainly going to be seriously challenged soon.

This isn’t to say the traditional practice model can’t survive the coming disruption and change. Tim and Martin managed to start, grow and sell a traditional model publishing group through the most disruptive decade in the history of media.

But while, amid the rise of the giant global media and information distribution platforms – Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and so on – Tim and Martin’s story isn’t unique, it is unusual. Even though Tim and Martin thrived, all around them many of their colleagues and peers fell.

Tim describes the week in 2012 when Fairfax and News Corp shed more than 3,000 journalists as the point beyond which the media sector was never ever going to be the same in Australia. Until that catastrophic week, many newspaper bosses had felt they could push on through the disruption.

Is being small and agile important, as Tim and Martin were? Interestingly, there are also some examples of large traditional media groups dodging, weaving, innovating and coming out with a sustainable and good business.

Channel Nine is an example: it accepted the fate of newspaper revenues and slashed this part of its business, it built a digital real estate classified business (better late than never) using its distressed newspaper assets, it risked going up against global streaming behemoth Netflix with Stan, and so far it’s still out in front of that bet, and it adapted it’s not insignificant broadcast assets in TV and radio to surround them with streaming channels.

Think about Fairfax and Channel Nine as businesses 10 years ago, compared with what the Nine Group is today, and you might get a sense of how agile you’ll need to be to come through to the other side of the coming changes.

The Nine group looks nothing like it did 10 years ago. Channel Seven does, and it shows. It’s a group that hasn’t changed much at all. It has a lot of work ahead of it still if it is going to survive, and its value as an asset of Kerry Stokes’s Seven Holding Group (which has a lot sexier assets in it than TV luckily) has plummeted.

You can imagine that, given the central role of GPs into our future of chronic care management, the private equity people swooping up corporate GP group assets have in mind the sort of reinvention of their newly acquired assets that Channel Nine achieved through media’s most disruptive decade.

So will Healius be able to reinvent itself with technology, adjacent acquisitions and some internal innovation the way Channel Nine did?

It’s feasible.

Despite what people tend to think about private equity (PE) – that they strip assets nine times out of 10 – they will often invest significantly strategically. The Healius PE team have a lot of avenues to invest strategically in emerging ares of opportunity:

- Servicing aged care far more comprehensively

- Developing both hospital in the home and aged care in the home virtual services, backed up by their network of GPs

- Developing new adjacent healthcare services off the back of telehealth – aka Babylon in the UK.

Remember, it’s not just the Healius group of GP centres that have been acquired by big money with intent like the above. And it’s not just PE footing the money to own larger GP corporates. Medibank Private owns half of the corporate group Myhealth. Fullerton Health, backed by significant Asian investors, is aggressively acquiring practice networks and has shown significant intent in terms of future models of care based on new technologies.

These big money rollup plays are just one competitor that traditional practices will need to face off against in the near future.

What else is likely to emerge that competes with the traditional GP practice model and it’s traditional business?

- A vertically integrated rollup of, say, a booking engine (HealthEgine?), a corporate group of GPs (any of many choices) – the people power element – a PMS vendor with a big footprint (Medical Director?), an few odd aged care management integration products (Telstra Health?) which could own all the own the most important parts of a patient’s data journey

- Private health insurance groups focusing on keeping their members out of hospitals and aged care institutions, through developing a version of their own primary care networks but more connected to hospitals and aged care

- Any number of new business models based on virtual care servicing and telehealth, such as post-cardiac-surgery management, longitudinal cancer treatment and management, virtual diabetes management, and so on. Babylon is a low-hanging-fruit, artificial-intelligence-driven telehealth service in the UK that is a canary in this coal mine: it has mobilised to take out most the low-hanging fruit of primary care money in the UK by automating the simple consults GPs used to have in the UK, making a consult vastly more convenient and cheaper for patients, especially younger patients who aren’t settled on a family GP. UK GP funding is being significantly disrupted by this new provider, especially among the millennial demographic.

- Public and private hospital out-of-hospital services, and aged care out-of-institution services. One distinct possibility for marginalising traditional GP patients is the public hospital system holding on to their transitioning patients and keeping them in their ecosystem for longer in order to ensure they are managed in a manner that helps ensure they don’t come back to hospital or don’t come back too quickly.

- Anyone who has a better convenience and cost offering: patients are likely to be far less sticky into the future to their traditional practice as a result of technology. There’s a bit of wishful thinking that is put about by the RACGP about continuity of care: that patients are best managed by keeping their same doctor so that the doctor has continuous oversight over their health over time isn’t in dispute. This is the best way for a patient to be managed, no question. But it is wishful thinking. The trend in the US and Europe, especially among millennial patients, is to convenience and price. As all the above services grow, and more useful data starts to flow to patients over the web, the idea that a person or family settles with one doctor, and maybe a second-tier local GP centre as a fallback, is going to break down, probably a lot. It is already starting.

The following is just a taste of some companies that are facilitating all of the above, most of which traditional GP practices have very little access to so far. There are lots more emerging where these ones come from, a sure sign that the cracks are widening in traditional models of care. The other common factor in these companies is that almost all are using web-based interfaces to share data between themselves, their networks and their patients seamlessly.

- My Emergency Doctor: clinics inserted between the emergency department of major hospitals and the traditional GP practice, to treat patients who are in need of emergency care but don’t necessarily need to go to hospital where they will cost a fortune to service. It is funded more by the hospital sector and uses cloud technology to make data sharing more seamless across its service and related hospitals.

- Doctors on Demand: One of a plethora of telehealth plays emerging, this one quite significant. Describes itself as bridging the gap between general practice and community pharmacy by providing 24/7 on-demand access to qualified Australian doctors and prescription medications when and where it is needed most.

- Osana: Membership-based model of providing GP care, funded in large part by hospital networks and private health insurers who want their members to stay out of hospital, or who want them to have quality continuity of care following an episode in hospital. Also uses cloud-based technology for its patient management and data sharing. Osana is working on the basis that, so far, continuity of care following a hospital admission via traditional practice is still largely broken.

- Cardihab: Digital cardiac rehabilitation: follows a patient out of hospital virtually and connects them to the right information and virtual care to ensure a much higher quality of post-operative rehab.

- CliniTouch: A digital platform that connects every provider in managing an aged care patient at home, or in managing a patient post hospital. Uses integration to EMRs in hospitals and with other providers to provide both patients and providers with important shared-data capability. This is a UK-based product not yet in Australia formally but piloting. It has some existing competitor products already in Australia such as Inca from Melbourne-based Precedence Healthcare.

- MediRecords: The first cloud-based PMS in Australia. Rather than servicing traditional GP practices, it is getting significant traction in fenced healthcare ecosystems, such as aged care, defence, and hospital networks. Its utility means data can be shared seamlessly between patients and all the providers in the ecosystem (Note: I am a non-executive director of this business).

- Clinic To Cloud: Cloud-based PMS for specialists that has taken up to 40% of the specialist market in just a few years

- Coreplus: Cloud-based patient-management software for allied health, primarily physios and psychologist, talking to some of the cloud-based GP PMS systems in order to establish seamless networking between GPs and allied health professionals on important patient data.

- Medi-Map: Cloud-based medication management solution out of New Zealand. Manages all aspects of medication in a facility-based environment – charting, administration, supply and communication – to facilitate a transparent, seamless cascade of care for residents in aged-care facilitates. Looking at connecting through some of the new cloud-based PMS vendor systems.

- HotDoc and HealthEngine: These two booking engines reach about 85% of all GP patients. Their core original function was booking appointments but they are moving upstream into more sophisticated patient management. They talk to all the current PMS systems for GPs.

Notice a common thread of all of the above merging businesses except perhaps the booking engines?

Each is facilitating, usually through cloud-based data-sharing technology, or threatens to facilitate, the eating away of what is the existing ground of traditional GP practices. Although booking engines are servicing the existing models of general practice, but they are interesting in that their technology and reach to patients can facilitate new models of care which will compete for traditional GP business. And they are agile.

The other key parallel in the medical sector you can see now, a parallel Tim and Martin could see in 2008 looming in their market, is the emergence of web-based platforms that can share data far more efficiently than traditional set ups.

In the case of Tim and Martin, it was a little unfortunate that both Facebook and Google decided to monetise almost wholly via advertising. These two platforms collect intimate consumer data to allow targeting of ads in a way no traditional media group could ever hope to achieve. Between these two platforms, more than 50% of all traditional media ads would go. Hence the carnage.

It’s not going to be quite so clear-cut in medicine fortunately.

But medical data platforms are starting to emerge; the government, rightly, is going to encourage the continuation of this pattern as they want more seamlessly flowing data in the system. And all the while, the big global platforms \that sent many of Tim and Martin’s peers to the unemployment queue and are lining up for a big slice of the medical market.

Eek.

Although it passed with little fanfare, a little over a year ago, Tim Cook, who runs Apple, announced at one of the company’s famous annual meetings that history will remember Apple as a healthcare company, not a mobile phone and computer maker – that’s how serious Apple seems to be.

At that time, Apple had already been pouring enormous resources into developing its mobile phone operating platform into a unit that they are planning will one day be the epicentre of patient data sharing and management. At that time, Apple turned all its mobile development might into centring its entire mobile health offering around the emerging healthcare web-sharing standard, Fast Interoperable Healthcare Interoperability (FHIR). Google, as it happens, is doing the same with its Android operating system and has similar designs on owning healthcare data globally.

Already in the US, and some European countries, your mobile phone can talk directly to your doctor’s patient management system to provide a patient with the latest and most relevant data they need to manage their health. It’s technology that isn’t quite here yet – all our GP patient management systems are essentially still running on legacy-server-bound architectures – but if you check the list of interesting companies out above, four of them are cloud-based patient management system offerings, all capable of doing it.

Another parallel trend is that government is moving with the new data-sharing technologies and platform plays that will underpin much of the change.

In Canberra and the eHealth departments of most of our states and territories, cloud is becoming king. It offers the potential of radical shifts in efficiency in delivering healthcare.

In the US five years ago, and the UK three years ago, both federal governments came out and mandated that their providers and technology vendors must go to the cloud over time. In the US the government mandated that within five years health tech vendors and providers would need to be FHIR and open API enabled to a certain standard, and if they weren’t, people could go to gaol.

The move by the US, having many huge global healthcare vendors of influence such as Cerner, EPIC and Allscripts, has resonated around the world to the point where even these big global vendors, which once wanted to hold on to the data in their systems to protect their commercial position, are introducing versions of their EMR-based products, which talk to the web seamlessly under the right circumstances.

In Australia, the federal government looks like it is about to move to do something similar to the UK and the US. They will probably give everyone five years to get their act together.

But if this happens, it will be a starting gun on very significant changes to the technology that Australian healthcare providers use. It will be mandated that eventually every provider must be able to talk seamlessly to other providers and patients, and vendor products will need to facilitate all this.

Despite all the mystery surrounding digital transformation and new technology, Tim and Martin’s media business, which they built to sell for 20 times what the PE guys at Cirrus Media could achieve for their long-time established media business, didn’t succeed through adopting some miracle new online technology.

Their business at its heart still a relatively basic and old media model, albeit one that has adopted modern digital channels for distribution.

It attracts audiences via a great stream of content distributed online, mostly by that oldest of old digital channels – email news – and they monetise their online community by inviting them to fairly traditional trade conferencing events.

Again, not a new media model. The thing that Tim and Martin did that practice owners might note include:

- They uncovered a rich seam of customer desire and need, and got obsessive in being the only group satisfying that need – in this case, really great content. When other media businesses were cutting back on content costs and throwing journalists overboard, they were doubling down to attract and gain the trust of a community of users. At the time it seemed risky. But they knew exactly what their audience (their key customers) wanted.

- They then simply invited that trusted community to come to events to meet up. The audience was much more comfortable with paying to go to an event – in trade media, and for the big consumer newspapers, free online news had trained consumers that they didn’t need to pay for online news. But they were happy still to pay for a conference.

It’s a simple business strategy and one that savvy practice owners will already know: stay close to your customers and within the bounds of government regulation, seek to fulfil their needs in ways that they can’t be fulfilled by your competitors.

To do this in the near future, practice managers and owners will need to understand what their competition is doing and the arc of where the opportunities will arise around cloud enabled providers and vendors.

One interesting thing about cloud-based technologies is that they can often level the playing field between small and large enterprise.

There isn’t any reason a traditional practice with a network of sites in one area can’t implement technologies that will allow it to connect to local aged-care institutions, allied health and even more meaningfully, to hospitals in the area, in order to capture some of the business that the big money is going to organise to sweep up. Some medium sized groups are already secretly piloting businesses like this.

It’s not easy, for sure. If you’re in Healius, you have capital to research and pilot new models of care that link your services much more closely with aged care and tertiary care. But the technology is not so expensive and clunky that a medium-sized independent practice can’t try it and try to corner the servicing of these new emerging markets in their own region with something that makes them unique to that region.

The secret to staying agile and being adaptable in this respect, outside of understanding the needs of your patients more than anyone else, is almost certainly going to be data-sharing technologies.

This is something almost no GP practice has today: Best Practice and Medical Director are where all your patient information goes. Both vendors are working on cloud products.

But even when they do, because our funding regime is based on fee for service, not outcomes, the systems haven’t been required to capture data in a format that could be used to fund an outcomes based regime. The systems can’t identify and track easily patients who are at increasing risk of diabetes or heart disease.

Meaningful data on longitudinal diabetes management, Alzheimer’s management, cardio management and other chronic conditions, tends to reside in the notes of these systems, not the shareable data fields.

This is a problem that the government is going to have to address soon. The massive opportunity of cloud based data sharing is the data you can generate. You can’t have a prevention or outcomes based regime of funding of medicine without good data. Ironically, New Zealand, the UK and many advanced HMOs in the US do collect this sort of data, and in those countries, outcomes are being funded.

In Australia, the political problem of Medicare being a sacred cow, and highly politicised, will be a big obstacle to come.

There is of course is nothing at all to stop Medicare simply moving its funding model from fee for service, significantly more towards outcomes, if we can get the data out of our providers. It’s just that any changes to Medicare always become a political weapon.

At this point, our major PMS systems have other, more immediate problems. They are both old server-bound technologies with very little capability to seamlessly sharing data with all the emerging cloud-based provider management systems, some of which are described above.

For the system to be truly efficient, all GPs will need to be using a cloud architected system eventually. Some are available now, but they are clunky because there are so many legacy providers and information sources that the new cloud vendors need to connect to. Cloud is designed to be connected to the cloud, not old server bound systems.

The trick now for a practice manager or GP practice owner wanting to continue and thrive is how they start to navigate what corporates, big-money rollups of GP services, private health insurance, and even public and private hospitals are going to start to throw at them in terms of disintermediating what has traditionally been their custom over the years.

Traditional GP practices aren’t going away.

But in 10 years’ time, the current distribution of GPs into GP corporates (about 25%), independently run and owned practices (about 60%) and other (15%) is going to be significantly altered.

Encouragingly, over this whole coming period of disruption, we are going to be needing a lot more GPs. So, the GP isn’t going away.

But general practices as we’ve known them?

A lot of that is going to change.

If the issues discussed in this article are of interested you Wild Health is holding a Cloud Healthcare Summit on August 10 which will be streamed live and is free to the streaming audience. You can check out the topics and panelists and REGISTER for the summit HERE.

If you’re interested in Tim’s book, Media Unmade, you can buy it HERE