The Department of Health finally wants to see some evidence of the usefulness of the MHR

If you trawl the health portfolio budget statement from March, on page 183 you will see a table that suggests the government is starting to lose patience with, and perhaps even faith in, the whole idea of the My Health Record (MHR).

The table says that as a part of measuring the performance of the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) into 2023, it is going to require that the agency “Establish an approach and trial baseline for measuring meaningful use via a ‘meaningful use index’ for My Health Record”.

What the government wants is for the ADHA to start properly measuring just how useful this $2.6 billion project is today, and moving forward.

Finally, someone wants some proof that the MHR is doing, or even starting to do, what we’ve all been promised it would do.

It should be shocking to us all that we’ve spent this much money and time and we haven’t actually been measuring usefulness for the entire life of the MHR project.

But MHR has never been in the public eye enough for anyone to seriously question how the project has been managed over time and whether, in relative terms, it was returning on its investment over the years. It’s always been political, used as a show project when needed for a bit of sparkle in health policy by the pollies and then sent to the reserves bench – more or less out of sight – when things got embarrassing, as they did after Opt-Out.

No one has really cared enough about it politically or publicly to stand up and say: “Enough willing that this thing will work one day, let’s put in place some proper audit and measurement of this project.”

Note: The Australian Office of National Audit has audited the ADHA and how it has implemented the MHR, but its remit was not how much the MHR is used or how much value it brought to the system. That might be about to change.

We should have cared more than we have because the idea of sharing healthcare data seamlessly and securely across our healthcare system, and giving patients access to their data in a meaningful way, is possibly the most important idea for the future of our healthcare system since the thought bubble that resulted in Medicare.

What may have got in the way of altering our attitude to MHR in the past couple of years was covid, and a changing of the guard at the ADHA at the end of 2019 – the entire senior management team left in the space of a few months, something that should have prompted a little more inquiry.

Not withstanding, some in government have quietly been trying for a reckoning of the ADHA and the performance of MHR for some time now.

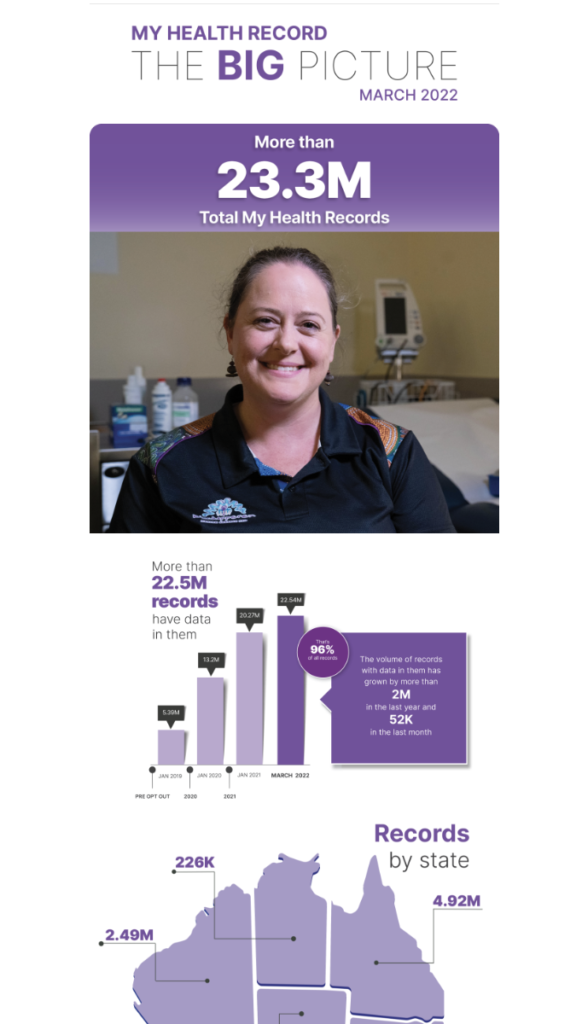

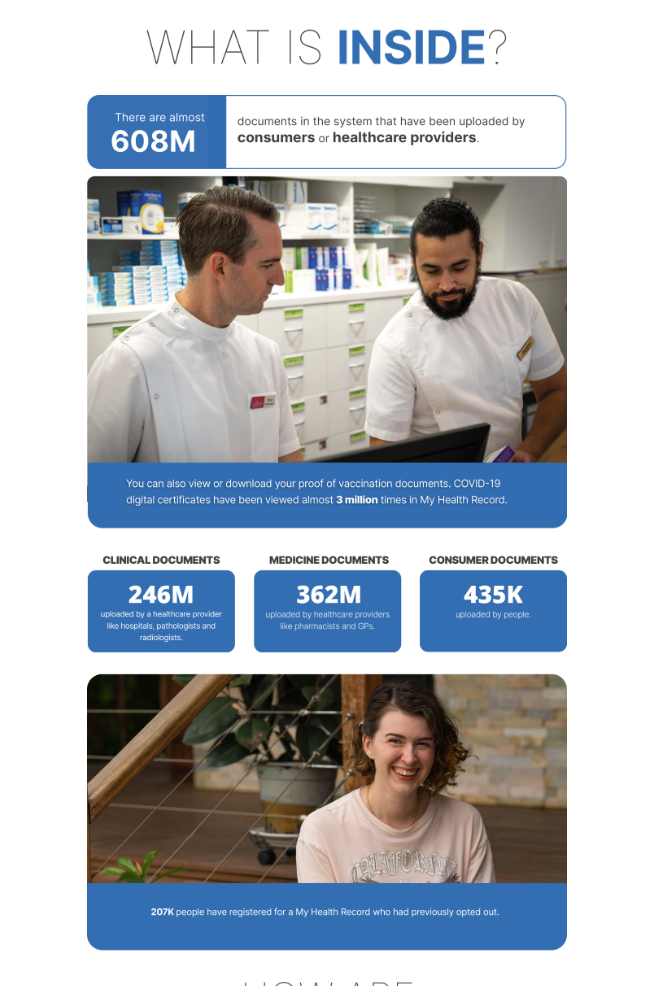

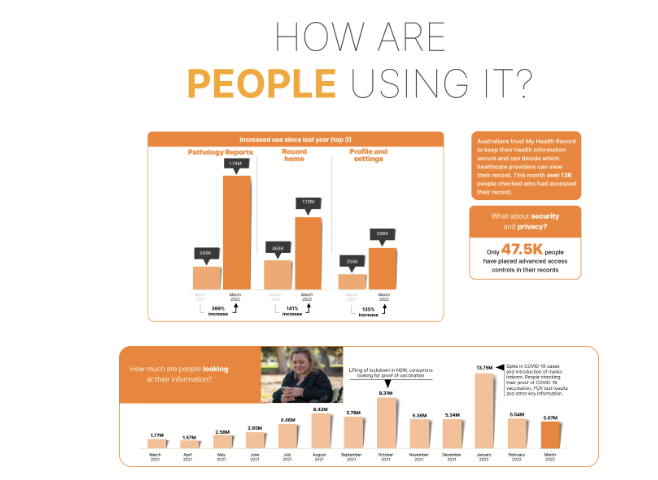

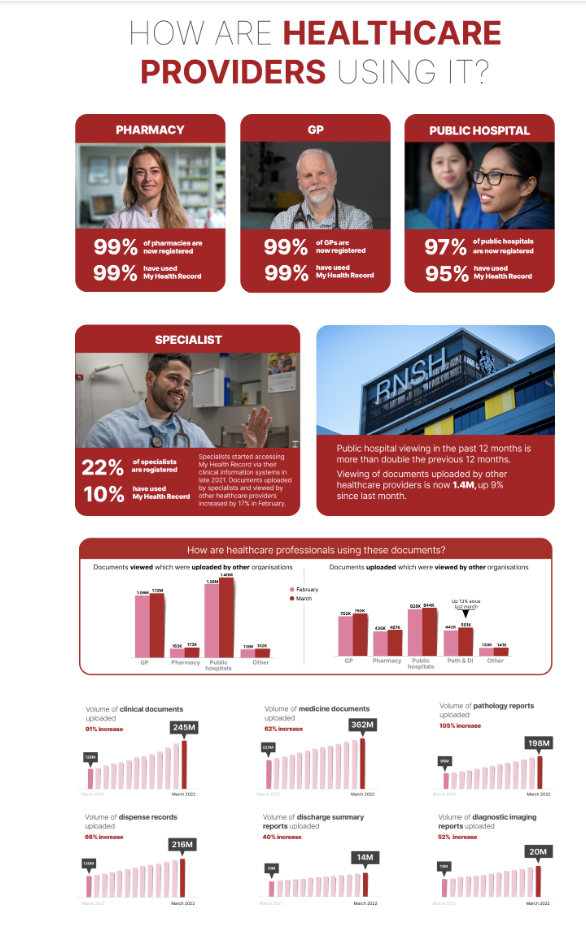

Check out these dazzling numbers (which have no baseline or reference points), everyone!

We’ve written a few stories in the past about the array of big numbers the ADHA publishes regularly, but these are meaningless because they never have a baseline or reference point and there is no attempt at all to frame them in some sort of return on investment to the public context.

It’s a long list of usually big, but meaningless, non-referenced “dumb numbers”. Without the context of a baseline, any of these numbers could mean anything.

Part of the problem we have is that the idea of the MHR is great: seamless sharing of patient data between providers and patients and patient empowerment with their own data.

With nothing else on offer, the ADHA can point to examples of patients whose lives have been changed by the MHR and doctors who will swear by it.

But how many patients and doctors use it each week or month, and how useful is it when they use it?

And even if we start, by sheer wait of money and effort, to get more doctors and patients using it, for the investment we continue to make in its technology, is Australia getting value compared to other approaches we could now take to this problem?

Here’s a very simple question, which goes to the “dumb numbers” approach of the ADHA, and which the Member for Bruce, Julian Hill, more or less put to representatives of the DoH, the ADHA and the AONA in a Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit hearing in Canberra on May 19, 2020.

How many GPs and specialists, as a percentage of the total population of each group, use the MHR every day, or even once a week?

Hill actually put the question this way:

“On uptake, the Auditor-General talks about 90 per cent coverage of the population under My Health Record. But it’s been put to me by practitioners that very few providers actually upload anything and that too many clinicians are not using the system. It’s been described as clunky and hard to use, and people just avoid it. If we’re looking at 90 per cent coverage of the population, we could expect 90 per cent of the data from medical appointments, tests and so on to be uploaded. In your view, are 90 per cent of the outcomes of consultations and tests being uploaded to the system? How do you know? How do you measure or assess uptake?”

This is the question of an innocent, wanting to understand quickly what is going on. Essentially, if we have MHR for 90% of the population, is it being used 90% of the time by our healthcare professionals?

As naïve as the question may seem, it’s the right question.

Here’s what Mr Hill got as his reply, from Bettina McMahon (then acting CEO of the ADHA): “In terms of uptake, I can provide you with some of our latest figures. We’ve seen a significant increase in the use of My Health Record by both consumers and healthcare providers, particularly over the last three months. In relation to general practitioners, the month of March has seen the highest amount of viewing of documents yet, as well as uploads to track use. We saw about a threefold increase in viewing of documents by general practitioners. Around 20,000 documents are viewed each month. That’s a threefold increase since the same period last year.

“We’ve also got 95 per cent of the public pathology labs — not private but public — uploading into the My Health Record, which is a threefold increase, again, over the last year of tests being uploaded. We’re seeing a significant viewing, particularly in general practices, of the medicines viewed. We’re seeing GPs look at current medicines and also a large increase in looking at pathology reports, discharge summaries and the Medicare overview.”

In other words, no answer to the question asked. Just a lot of meaningless numbers thrown outwards with reasonably gay abandon without any baseline for reference.

Mr Hill again, in reply to the ADHA CEO:

“That all sounds very interesting, and it’s nice that more people are using the system. That sounds positive, in a sense. But the thing I’m trying to understand is how you measure the total uptake. What are your assessments of what percentage of GPs are actually using the system of specialists? You mentioned a figure of 95 per cent of public pathology tests, but I’m trying to understand that, whilst the trajectories are positive, it could be from five per cent to 10 per cent, which is not a great story, or it could be from 70 to 80 per cent, which is a lot better. How do you measure it in terms of the total number of consultations and interactions that are being had? I suppose that’s trying to get to the question: what evidence is there that it’s achieving the high coverage really necessary to achieve the overall benefits?”

And there, nearly two years ago now, we see that government wasn’t buying ADHA spin anymore.

Hill is pleading with the ADHA to just tell him what is actually going on in terms of use by providers and patients. And the ADHA is fobbing him off with more unreferenced numbers.

That was almost two years ago. Fast forward to today, and we have the same “dumb numbers” being published with no reference points or baselines, so no one has any real idea of what is going on.

Actually, not quite true: if you dig around, you can occasionally get hold of some numbers out of the ADHA that strongly suggest that very little is going on in terms of healthcare provider use.

For example, in that 2020 hearing the ADHA meant to impress the hearing by saying that almost 20,000 documents had been viewed in a recent month by GPs, and that was a threefold increase on the year before.

If you break that 20,000 number down, according to the ADHA, about half our GPs are viewing an MHR once a month (note: this was in May 2020).

Is that meaningful?

If we want to help out Mr Hill and the audit committee a bit here, that translates as one look-up of an MHR every 90 times a patient visits a GP (based on total GP consultations in Australia per month).

That makes the answer to Hill’s original question, of total relative usage of the MHR by GPs, about 1-2% of the time – at best.

So much for having 90% penetration of GPs as an impressive figure. Ninety per cent of GPs might be able to access it but it’s accessed only 1-2% of the time on a per consult basis.

Of course, that’s only GPs, who make up less than half of doctors operating in the community.

So far, MHR has hardly penetrated the specialist sector (22%, according to the ADHAs latest “dumb number” report). So, we might be talking more like 1% use or even less in terms of use by doctors in the community on a per consultation basis.

A couple of other relevant points if we are talking meaningful use:

- the almost 20,000 GPs per month figure mentioned by the ADHA back in 2020 was quoted shortly into the covid pandemic, which very likely spiked usage significantly

- Even if doctors are using the MHR 1-2% of the time, we have no idea what they used it for, and whether its use was actually “useful” – to the doctor during the consult, and overall, to the efficiency of the system.

- It’s not clear what a GP “view” actually means because it isn’t described anywhere. Certain GP practice staff have to access the system several times per month to upload patient summaries so a practice can get an e-PIP payment of up to $50,000 per year. Is this part of the usage and views being reported? If it is then we are reporting a negative as a positive – a GP wasting time away from patients uploading data, as a MHR view. A lot of GP practices have admitted off the record that they have automated the patient summary upload process to the minimum specification of what is required, and in doing so, are uploading information that is near useless. Are we measuring this?

Bad maths and logic, you reckon?

At least I’m trying to apply some maths and logic to a basic question people have wanted the ADHA to answer for a long time now.

The ADHA so far just keeps on churning out “dumb numbers”.

But the lots of “dumb numbers” tactic, it seems, might have a use-by date now.

DoH asks for a ‘meaningful use index’ of the MHR

In the March budget portfolio papers for the DoH, the department has outlined that over the next 1-2 years it requires that the ADHA develop what is being termed a “meaningful use index” of the MHR, which will include a “baseline”.

The department wants the ADHA to first establish a “baseline” – of usage by providers and patients, we presume – and from that point achieve an increase in healthcare professional cross-views (where one professional views the record of another) year on year of at least 20%.

The budget paper indicates two other methods of measurement that should be developed by the ADHA:

- Establish an approach and baseline for measuring annual estimated digital health benefits realised.

- Establish [an] approach and baseline for measuring cost-effective digital health infrastructure through a partnership value index.

We asked both the DoH and the ADHA for any other detail they had on this measurement initiative so we could understand if such indexes might actually be workable.

The DoH didn’t have any but the ADHA got back to us and said that the indexes were now being developed and would be published in the Agency’s Annual Corporate Plan in August this year.

But we probably don’t need detail to understand that we are 17 years and more than $2.6 billion into the MHR project (starting with the PCEHR), and we forgot somehow to ever set up any processes to effectively measure:

- How much it is really being used

- How much it is being used effectively

- How much its use actually returns value to the healthcare system

According to the DoH budget papers, within another year or two, we might have some sort of system to start measuring use and return properly.

Two years more before we start working out if the MHR is being used and working properly or not?

It’s not rocket science to work out how much the MHR is actually being used.

It can probably be done within a couple of days, or less, with data the ADHA has access to but doesn’t publish.

Really, someone in power should just demand this is done, pronto.

Working out how much return that use is bringing to the system (how useful in relative terms it is) is going to be a lot harder.

That’s not meaningful use, THIS is meaningful use

Most punters won’t be following what is going on with patient data access and sharing in the US, so most won’t have come across the origins of the term “meaningful use” in the context of healthcare data.

Most punters look at the US, see disastrous healthcare outcomes, and dismiss the idea that we can learn anything from that country in terms of improving our healthcare system.

But all of us punters would be wrong in making that assumption.

Precisely because the US system is so messed up – mostly by its private payments regime – is why the US government has had a co-ordinated, innovative and bipartisan approach to developing much better patient data access and sharing for almost two decades now.

And the approach is now starting to pay off in a big way.

Five years ago, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), which is the US equivalent of our ADHA, managed to get the US government to pass legislation that forced every healthcare provider and software vendor to start upgrading their technical capability to share data across the US system seamlessly to common web-based standards.

Part of that standards program included Fast Interoperability Healthcare Resources (FHIR), a modern and fast-evolving web-based healthcare data-sharing standard that works in tandem with other key health data standards such as HL-7 and which, ironically, was founded and mostly developed by, Australians.

The legislation put in place in the US was the 21st Century Cures Act.

Because everything was such a mess, and the medical software industry had to undertake such radical change involving so much new investment, the ONC gave everyone five years to upgrade, and embarked on a co-ordinated program to help providers and vendors on the journey.

In April 2021 that legislation came into effect and most vendors and providers had upgraded their data-sharing technology to the point where most had a basic modern and standardised data web-sharing interface surrounding their systems, so data could be shared with other providers, and, most importantly, patients.

But sharing was never enough for the ONC.

Underlying the whole program objective was what the ONC termed many years ago “meaningful use”.

At its heart, “meaningful use” meant that it wasn’t enough that every healthcare provider had systems in place that allowed secure and distributed sharing of healthcare data. That data had to be sharable in a manner that would make it immediately useful to both other providers and patients.

The ONC set standards around use, so it all could be measured as things moved along, something we forgot to do in Australia with the MHR.

From the very start, the ONC based their whole program on the idea of performance and measurement around “meaningful use” of data.

“Meaningful use” meant exactly what it said. In fact, if by April last year you were not able to share data in a basic and “meaningful” manner, you could technically be sent to prison. The ONC is run by a pretty smart and high-EQ team, so while there was stick in this process, they managed to make the whole program have a community feel.

Fast forward to Australia’s current and ongoing effort to share healthcare data and the DoH’s recent introduction of the term “meaningful use”.

There is very little description as to what the DoH actually means by a “meaningful use index” but it isn’t what the ONC in the US means.

The DoH wants the ADHA to somehow develop an index that measures how much the MHR is used firstly, and then how much value that use returns to the healthcare system.

These two measurements are very different and they aren’t what “meaningful use” is in the US.

The DoH wants to be very careful in directing the ADHA so it concentrates its efforts mostly on “value” to the system, not just on use.

We know already from how GPs are gaming MHR patient-summary uploading that use and volume can mean absolutely nothing in terms of creating value to patients and the system.

What if the MHR isn’t working after we start measuring it properly?

OK, so we’ve built a $2.6 billion centralised citizen health record and never thought to establish baselines of measurement of use, performance and value to the system.

And now we want to measure it, after 17 years of building it and thinking it feels like a great idea that should be working.

What if it isn’t working and the new index makes that very clear?

The DoH and the government are trying here, as it is clear they are getting frustrated with the “dumb numbers”.

But there is a pretty big political flaw in the DoH approach. Everyone is wanting, assuming, thinking that the MHR is a good idea and should be able to work.

The ADHA has built and runs the MHR and is charged with making it work in the eyes of the public. Many (most?) in the ADHA believe in the MHR and are committed to making it work.

Will they really quickly build a working robust “meaningful use index” that could potentially expose MHR as not being that useful in relative terms, and a poor investment?

Technically, the ADHA has the data to work out the exact answers to the questions asked of it by Julian Hill and that Parliamentary Audit Committee in 2020.

It’s highly probable the ADHA will have understood actual usage for a long time now and, not loving the numbers, keep trying to buy time by publishing its “dumb numbers”.

So are they the right people to develop a “meaningful use index” or should that really be the job of another independent group, like the Australian Office of National Audit?

The MHR is the wrong solution to healthcare data sharing

If you put the MHR up against the strategies of other countries that are moving at pace on the idea of much better healthcare data sharing, there is no debate to be had about the MHR being an outdated healthcare-data-sharing technology and concept that it isn’t user friendly, is a huge security risk and is not adaptable.

In 2020, less than 1-2% of doctors were using it. The usage is that low because MHR is not useful to doctors. It isn’t seamless, fast, easy to use and patient friendly. It’s bureaucratic, clunky, slow, hard to use and the information in it is in such bad format that it’s very hard for a doctor to use in a meaningful way.

We don’t need to wait for another 1-2 years and go through the excruciating spectacle of the ADHA developing what in effect will be a non-meaningful meaningful-use index, and then attempt to sell it to us all.

The MHR does have some use, and can help us in a healthcare-data-sharing journey, moving forward. We can learn from the experience and use parts of the infrastructure to help us, moving forward.

It’s not all a write-off.

A spokesperson for the ADHA told Wild Health that “for many people the MHR can be life changing and life saving.”

It almost certainly can be. But that isn’t the point. The point is, what is the best approach and technology this country can take to enable better healthcare data sharing in a manner that is optimal to both patients and doctors.

If Australia only has the MHR to work with, of course some doctors and patients will use it, and swear by it. And more will over time.

But it’s still the wrong approach and technology.

Some good numbers?

In the latest set of MHR “dumb numbers” report, in the section, ‘How Much are People Looking at their Information’ it says that in January of this year 13.75 million people “looked at their information”.

This number isn’t entirely “dumb”. Of the 22 million MHRs with data in them, this number represents a lot of patients checking their MHR – mostly for their covid vaccination certificates and PCR test results. It’s not 13.75 million checking individually. The number is total views, so it might be 4 million coming back on average three times. Not withstanding that is a lot of people now starting to use their MHR.

Was it useful though?

In terms of covid and checking vaccination certificates or PCR results, most of the action happened outside the MHR. If you were developing a robust meaningful use index how then would you score the MHRs value in this process, given it was handled easily outside of the MHR platform anyway?

These are the hard questions that the DoH and the ADHA would need to be asking themselves if they do develop a proper “meaningful use index”.

Technology has moved on significantly from the MHR concept

Big patient user numbers or not, the MHR is not the way forward as our central piece of health-data-sharing infrastructure anymore.

Australia needs to start paying attention to what is going on in the US, and some other interesting smaller countries in Europe, where modern distributed data sharing technology has either been introduced in one go by smaller-country non-federated governments, or, in the case of the US, which is fragmented and messy like us (but on steroids), has been introduced via guiding and facilitating all healthcare providers and software vendors over time to adopt common and modern data-sharing technology.

In such a set-up, patient data is not held or managed centrally, which makes sense in a whole lot of ways. As patients move around the system, each provider has technology that enables them to share that data directly and securely with their patient at the point of care, or with another provider anywhere else in the system, when needed.

Because the data is accessible across the system, the innovation in the US – as far as patient side apps to help patients manage their data the way they want to manage it – is massive.

Distributed data-sharing technology using the cloud makes a lot more sense from an administrative and security angle. In Australia, the MHR is a honey pot where we hold everything on every patient in one place, and because of it being centralised, every provider has to have access the MHR to send it data and access it again to get back data. This sort of data architecture is literally from the late 1980s.

In a distributed system, such as the US’s, data is held at those points in the system that the patient interacts most with. In this way a patient is far more likely to see and use data that is most useful to them.

In the US a patient data record isn’t one mass of everything you can get your hands on located in one spot (as the MHR is). Such design will always cause large issues with access, organisation and finding the right data at the right time.

Data in a modern cloud-distributed system is exchanged on the basis of how useful it is at any point of a patient’s care cycle, so the most relevant data is always prioritised, and more accessible.

Tell-tale legacy technology base in Australian health

If you’re finding any of this hard to fathom – that we could be so backward – then ask yourself why every healthcare provider and software vendor in the US is enabled with some form of cloud-based data-sharing technology interface or system, and about 90% of Australia’s providers, especially those in primary and specialist care, but lots of hospitals as well, work on outdated server-bound data platforms that had their heyday in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

This older technology locks data up, yet our entire healthcare system is running on it.

Another way to look at how backward our healthcare technology has become is to simply ask yourself: why does my banking app, travel app and accounting app all work seamlessly to provide me valuable live data sourced from multiple distributed systems (cloud held data), but virtually none of my healthcare apps are able to work this way?

Note: you will have mobile health apps, but the only one that really works using this technology is the one that accepts a token on your phone from your GP patient management system, which allows you to pick up your script anywhere in Australia. Everything else is web-based apps trying and failing to talk to healthcare provider systems which have data locked deeply inside their on premise server bound technology.

What should we be doing?

The first step for Australia to get its health-data-sharing technology back on track is probably to do what the US did five years ago and introduce real “meaningful use” data-sharing regulation or legislation to start all our providers and software vendors on a journey to standardise on modern web-based data sharing standards.

Trying to develop a “meaningful use index” of the MHR after so many years of not measuring anything, when the data is already there to establish the reality of its relative poor usage today is just kicking the can on modern and effective healthcare data sharing down the road a bit more.

The MHR is an idea and a technology that hasn’t worked, and no amount of trying to prove it can work is going to make it work.

By the way, if the MHR is the only thing patients and doctors have, of course we will end up with providers and patients using it over time, some even swearing by it.

Without anything else in play what else can happen?

But Australia is now starting to get embarrassingly behind other developed countries in rolling out fast and effective healthcare data sharing.

We need to step back, get perspective on what technology is really working around the world, and make a plan that evolves the MHR project into something far more valuable to Australian healthcare providers and patients.